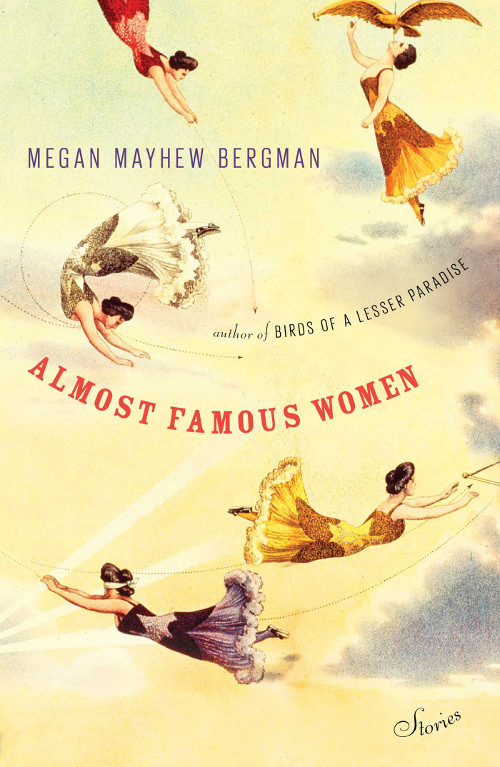

In her second story collection, Almost Famous Women, Megan Mayhew Bergman delves into the lives of real women who skirted the fringes of fame, feminism, femininity, and polite society, looking at the ripple effects of both the choices they made and the ones that were made for them. Conjoined twins, a self-destructive painter, the illegitimate daughter of Lord Byron, a jazz great with hustle, a war vet at Femme Beach: these are women grounded in their bodies by more than their sex, who are low on options and defined by others—as a freak, a “do-anything girl,” a pretty mermaid, a “high-grade bitch.” But in these stories, these predefined women are given voices to define themselves. The collection spans decades and continents, races and ages, and Mayhew Bergman has managed the perfect note throughout for a collection that links the stories thematically but never feels repetitive.

One of the most impressive traits of Mayhew Bergman’s writing is how fully she imagines these characters’ lives. Many of the stories center not so much around the almost famous women such as musician Tiny Davis, but more around the women behind those women, the ones who drive the buses and make the sandwiches, or maybe the woman who is even one level further back: not Vivien Leigh or even Butterfly McQueen, but a young girl who tries to convert Ms. McQueen to Christianity one winter afternoon in Augusta, Georgia.

“Saving Butterfly McQueen” in many ways exemplifies Mayhew Bergman’s many strengths. McQueen is the actress best known as Prissy in Gone With the Wind, the maid who says, “I don’t know nothin’ bout birthin’ babies!” and the story involving her opens in a medical school lab where the main character, Elizabeth, remembers an event years before, when her white youth minister (who refers to McQueen as “Prissy,” not even affording her a real identity) sent her to McQueen’s door to convert her. Far from being converted, though, McQueen tells Elizabeth she doesn’t believe in God, that she “won’t be anyone’s trophy” and plans to give her body to science. McQueen thus opened the tiniest door to the doubts that ultimately brought Elizabeth to where she now finds herself after many years, about to cut into her first cadaver. Thinking back, she wonders whether McQueen really did end up giving her body to science. “Donating [one’s body] to science was about taking control of the thing that was undeniably hers. Had that chance been taken from her? There were only so many ways to show the world that she was more than a petite maid cowering on the stairs underneath Vivien Leigh’s raised palm.” This would be a satisfying enough ending, but Mayhew Bergman keeps pushing, wringing as much as she can from these characters who are deeper than the reader at first imagines. Cutting into the cadaver, Elizabeth thinks, “Me—I’m afraid I’ll become one of those doctors who sees a patient and not a person, the body and not the spirit. What I hope, I guess, is that the right kind of callus will form around my heart.”

Each story turns and twists various strands of human emotion while asking smart questions: what does it mean to be connected to another human being? What is autonomy? Do we need trauma for art? What are the effects of war? At an over-arching level the collection impressively wrenches nuances from thematic links between stories, but even at a line-by-line level it is a pleasure to read, the writing itself lush and grounded, as in this paragraph from “Norma Millay’s Film Noir Period,” written from the point of view of Edna St. Vincent Millay’s sister:

Vincent and Kathleen share the bed, their downy knees and sharp elbows pushing at her back and legs, which she resents and cherishes all at once. The smell of their bodies, not so frequently bathed in winter, is familiar, something like lavender soap, sweat, and pine sap, which falls into their hair when they collect kindling for the stove. She loves knowing her sisters are by her side even as Cora [their mother] leaves in the dark of morning with an ugly brown coat buttoned over her uniform. “You’re a tribe,” she told them years ago, on their first day back to school after typhoid fever, when she’d cut off their hair and they looked like pale, starving boys in white dresses. “You stick together.”

Finally, Mayhew Bergman struggles with the question of what to do with such women, who won’t listen to reason as defined by someone else, who are willing to follow their bodily desires. She writes, “Maybe the world has been bad to its great and unusual women. Maybe there wasn’t a worthy place for the female hero to live out her golden years, to be celebrated as the men had been celebrated, to take from that celebration what she needed to survive.” In this collection, such great and unusual women have found their worthy place.

Almost Famous Women, by Megan Mayhew Bergman. New York, New York: Scribner, January 2015. 256 pages. $25.00, hardcover.

Erin Flanagan is the author of two short story collections published by the University of Nebraska Press: The Usual Mistakes (2005) and It’s Not Going to Kill You, and Other Stories (2013). Her fiction has appeared in Prairie Schooner, Colorado Review, The Missouri Review, The Connecticut Review, the Best New American Voices anthology series, and elsewhere. She’s held fellowships to Yaddo, The MacDowell Colony, the Sewanee and Bread Loaf Writers’ conferences, and this summer served as faculty at the Antioch Writers’ Workshop.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

Leave a comment