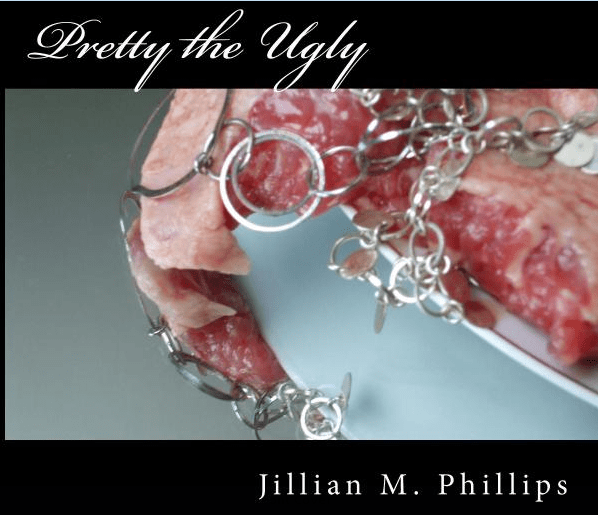

Pretty the Ugly, Jillian M. Phillips’ collection of poems, poses with its very title the question of whether the contained poems will center on the ways we see the world, or the means and methods we use to manipulate ourselves in order to look better to those who see us. From the first poem’s last phrase—“I forgive you”—it becomes clear, however, that this chapbook will neither merely contemplate nor cut skin-deep, that the critical question it asks of its reader it will also ask of itself: how do we damage ourselves when we pretty the ugly?

This finalist in the 2013 ELJ Publications Chapbook Competition is slim: twenty-five mostly brief poems separated into three parts—“The Onslaught,” “Scrambled Bodies,” and “Truths Like Tassels.” Progression through the book is without artifice, as section titles are drawn from an included poem’s title or actual language. But the poet isn’t prescriptive in her structure and instead maps a compelling territory of forgiveness that yields to the reader through its accessibility in tone and form, and the singularity of documented experiences, reflections, and calls to action.

The first section, “The Onslaught,” focuses on the physical world and on our efforts to beautify the evidence of dishonesty and disloyalty that we observe on permanent cultural display. The need for reinvention is focused on these structures that stand firm in the face of punishing emotional and environmental aggression, and the dignity we often assign to these ardent monuments. Possessed of storms that batter the self and relationships that erode intimacy, these initial poems assert that contrary to the notion of endurance as elegant, “Immortality is in the remaking,” and forbearance lies directly in the path of destruction, as “even concrete can be broken.”

A poem like “Traveling” makes it clear that there is little grace in abiding, that staying “is stopping, drowning / in what you have kept / afloat,” and that the “language of leaving / is fluent and fluid.” Motion, therefore, is not only espoused for safety, but for sanity:

It’s the staying

that sticks in the craw,

the art of letting go without

going anywhere.

Whereas forgiveness is “a foreign land / with its own currency / of love forever / exchanged without loss,” staying and pardoning means sinking and condoning, means trying to negotiate with time: a force that not only corrodes, but diminishes and robs.

The consequences of absolution emerge in the poems of “Scrambled Bodies,” most evidently in the well-placed “Pretty the Ugly” pivot point. In length this piece is a departure, as is a narrative that disarms by sidling up close before spinning away and dragging the reader’s eye to the “grotesque spectacle” of “ihateyou and lookwhatyou’vedone things” and forcing a confrontation with the notion of release from blame through explicit and often sexual imagery about the price we pay when we try to “make the savage serene”:

You’ve dressed it up in bows and curled its blond hair,

made it a delightful Shirley Temple tap number,

and Oh! How cute it was! And maybe you threw up just a little bit

trying to reswallow the saccharine bullshit.

Because we recognize that we have made this attempt before—“killed the things inside.” Our intent to protect others from our inherent ugliness has led us to pardon, but rendered us guilty of quieting our voices to the point of silence and diminishing our own brutal beauty to the near-absence of selfhood. We have freed others from blame or guilt but in so doing have also subsumed responsibility in such a way that we “will always remember / what [we] could not let live,” and find ourselves at:

the part in the slasher movie where the serial killer

takes off his mask of human skin

to reveal an attractive face.

Taking on an almost elegiac tone, the poems of “Truths Like Tassels” confronts the role of honesty in forgiveness’ “danse macabre”:

We are separated

by the veil of niceties, could be priest and sinner,

the bell and the sexton, but more—we are lonely

and starved for absolution, paying our penance

to watch the peep show. We dance for each other

in our little booths, shaking our truths like tassels.

And it is in these dark places that we find not forgiveness, but truth. Because “we do not pretend when we are blind” and are not distracted by the sun’s “false livelihood”; we don’t have to feign interest or simulate appropriateness in these dim places of confession. To recognize that we see clearly—“the ghosts as well as the living”—when we are disadvantaged is to accept that what we perceive as beautiful is so because it is tragic.

Ultimately, forgiveness requires bravery: to risk ourselves in terms of both what is taken from us and what burdens us. Finding truth means making an active choice to explore the catastrophe of beauty—the physical elements of assault, the self-destructive byproduct of absolution, and the ornamentation of truth:

we realize that courage

is just another word

for honesty and make the decision

to find our own truths.

And how will we know when we have succeeded? When “taking the risk of being wrong” leads to the “uncomfortable places within” that cannot be defined in polarizing descriptive terms, or by a singular sense of truth? Pretty the Ugly has certainly succeeded. This incisive chapbook achieves an almost discomfiting ability to poke and comfort and provoke and calm within the span of mere words. The distance from poem to poem and between ugly and pretty appears minor, but the implications of this reinvention—the harm we do ourselves in attempting to achieve the transformation—comes at the price of forgiveness.

Pretty the Ugly, by Jillian M. Phillips. ELJ Publications. 50 pages. $12.00, paper.

Erin McKnight is the publisher of Queen’s Ferry Press, an independent press publishing collections of literary fiction. Erin’s own writing has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and W. W. Norton’s The Best Creative Nonfiction. Erin lives in Dallas with her husband and young daughter.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

Leave a comment