Sophie Klahr & Corey Zeller’s There Is Only One Ghost in the World may have found life in the middle of a pandemic, but their collaborative book doesn’t steep in the tedium of socially distanced landscapes. These two writers instead tie a balloon to the narrative and gaze at contemporary America from a bird’s-eye view before descending onto character’s shoulders and floating back up again. Klahr & Zeller trade traditional narrative styles for a patchwork of postmodern American tragedies sewn together with the meticulous needlework of poetic prose.

Each one-page vignette, oftentimes alternating first and second-person narration, reads as reminiscent letters passed among two friends: “the concrete floors of your loft were painted red. When you’d relapse, I’d sit outside the heavy metal door, sliding notes and chocolate bards underneath once a day.” Every vignette opens with an innocuous thought before meandering through each narrator’s stream of consciousness and landing at the crux of existential and philosophical epiphanies. Some vignettes meditate on missing women’s posters in Iceland, trans men’s menstruation, the day when the only thing left of our parents will be boxes, and a time before humans touched the earth. Other vignettes zoom into scenes of rehab movie nights, Capitol riots, monoliths in the desert, AA meetings, crime scenes, and casinos with slot machine names like “Pompeii” and “Lady of the Dead.”

Klahr & Zeller frame the book in such a way that, even though the narrative follows no obvious trajectory, it captures, by the end, an arc of unabashed hope in the simplest joys. In the first vignette, the narrator grapples with the naïve hope that, despite their beloved neighbor’s death in a house fire, the puppy survived by plunging itself through the window: “Only when I was grown-up did I realize that it couldn’t be true, that the puppy could not have broken the glass. I asked my mother, and she admitted: it wasn’t true.” The story is one about the tales we tell our younger selves in times of unfathomable tragedy and the disillusionment of realizing cruel truths we were once mercifully spared. The last vignette, though, recaptures a state of hope for impossibility. A blind donkey dances to gospel music, and scientists fulfill a mummy’s dying wish to speak again; there there’s hopelessness and suffering, there’s also ineffable moments of joy in the act of “swaying until the song is over” and finding our voice even when it’s too late. What makes the book all the more poignant is that it isn’t a sum of its beginning and end but rather of the kaleidoscopic portrait of American solitude and solidarity.

The shortest of Klahr & Zeller’s vignettes may span a mere two lines, but make no mistake: the prose stands out meaningfully against the page’s white space. The lines read, “You keep having the hope that this is a prologue but no one knows how far they are into their own story. Some of us are hoping it’s the end.” Klahr & Zeller nestle these words, never didactic or heavy-handed, between two vignettes. In the preceding one, a lady, who often feeds pancakes to a wild turtle, watches as a man runs off with the creature one day. The narrator writes, “I confess that I wish I believed in God, and you say Just then, I was praying for you.” We are, at the same time, merely the reader and the far more abstract “you”—the relentless hope in spite of the unknown. In the following vignette, a narrator recalls the old teddy bear from a late first cousin: “She died alone in her apartment and no one knew for days . . . At some point, long before my cousin died, I’d had my mother clip the thread that held my bear’s mouth. I wanted the bear to be able to show herself. To show if she was happy or sad. Or whatever.” We’re, once again, caught in the white space, or the crosshairs of sentiments about unwavering optimism despite all odds and tragic, silenced ends.

Perhaps the most delightfully confounding vignette of the entire book is the one in which a death-row warden serves Ricky Ray Rector his last meal:

He gets a steak, cherry Kool-Aid, and a piece of pecan pie. He asks one of the guards to save his pie so he can have it after his execution . . . One guard thinks about Heaven’s Gate when she hears the request. Didn’t Kool-Aid have something to do with that choice, with all those people who died in their matching sneakers? . . . Victor Ferguer . . . What did he request for a meal? A single olive . . . After his death, police found the pit in his pocket. The hard whisper of a tongue.

It’s no skeleton in America’s closet that we sensationalize murderers and the world beyond crime scene tape, but the authors extend to us a contemplation of humanity in the most monstrous and familiar faces. After all, that monsters are human is what disturbs us to our core and complicates our sense of morality. Ferguer himself even kept the olive pit in hopes that a tree, a peace offering, would sprout from his grave. Klahr & Zeller invite us to contemplate our own last meal and what we may leave behind once we’re gone. The book’s moral ambiguity speaks appreciated volumes to our human existence, which is already ripe enough with profound uncertainty and impending mortality.

Klahr & Zeller wrote the book, in a shared document, within a span of eight months during the height of what was, for many of us, the most historical and uncertain time of our lives. Even so, There Is Only One Ghost in the World doesn’t tread the overwrought trend of quarantine life and wistful recollections of the Before Times. The authors tell us not only that “the world is dense, intimate, and strange” but also that there is hope in the most ordinary places of hard times and uncertainty. We’re all just one ghost in a world of other ghosts trying to send us letters like these, and I’m waiting at my mailbox every day for more of them.

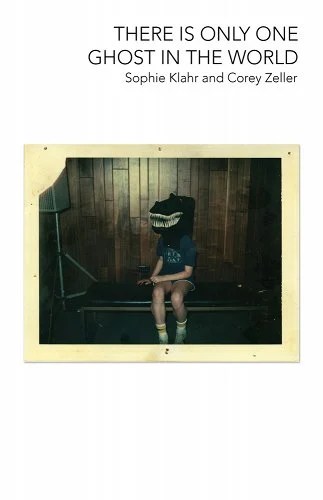

There Is Only One Ghost in the World, by Sophie Klahr & Corey Zeller. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: FC2, October 2023. $16.95, paper.

Shyanne Hamrick is a writer and poet. She’s an English graduate student at Winthrop University. Her curiosities range among classic rock, horror, mythology, true crime, and magical realism. When she isn’t writing, you’ll find her in intense board game sessions with her family or on the porch swing with her dog, Pumpkin.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

Leave a comment