Easy to Advanced Hand Puppets

Introduction

When was the last time you made a hand puppet? Or, for that matter, when was the last time you did anything? Something real. Be honest.

Right, okay: then you might as well make hand puppets.

And for that, you’ve come to the right place: an instructive, easy to follow how-to guide for numerous hand puppets that can be crafted from items you have around the house or can easily find nearby.

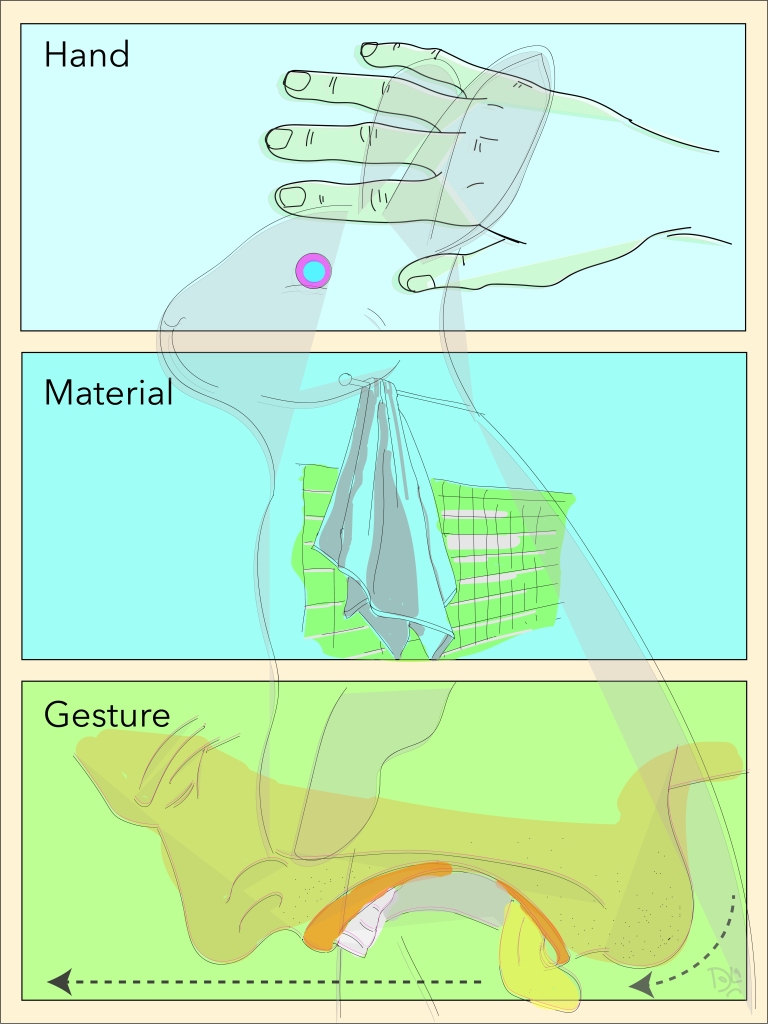

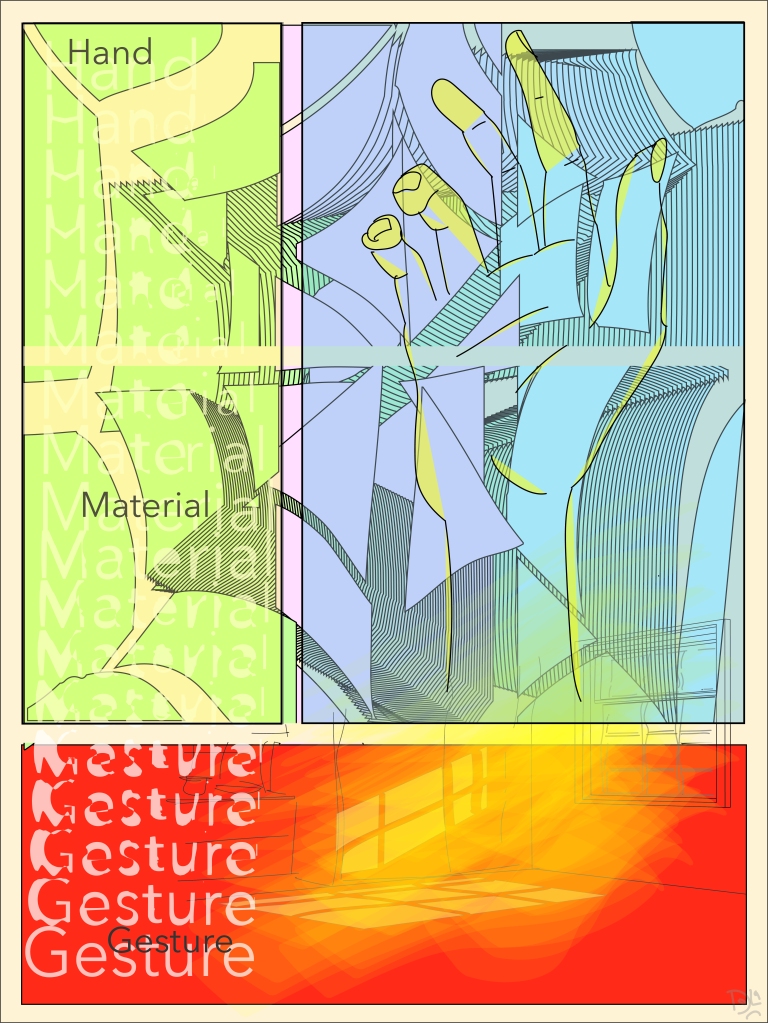

Making hand puppets is simpler than you think. They require only three parts: a “hand” that goes inside a “material,” and finally the “gesture,” that crucial movement by the operator (you) which breathes life into all to make a character. There’s nothing else to it.

This reference guide will illuminate through straightforward instructions the surprising variety with which these three elements—hand, material, gesture—can be mixed and arranged to form novel identities.

Helen Haiman Joseph, often regarded as the grandmother of American puppetry, said of the great George Sand’s approach to the art: “Her feeling was that when she thrust her hand into the empty skirt of the inanimate puppet it became alive with her soul in its body, the operator and the puppet completely one.”

Puppeteer, it’s up to you to decide if becoming one with the garbage around your house and in your life is a gift or a curse. Follow the easy steps below to lose yourself and find out.

1. Hungry Rabbit (Easy)

To construct the Hungry Rabbit puppet, you’ll need only to find an old cloth or rag. A used napkin will do in a jam. Simply grab the cloth and pinch two lengths upward through your fingers for the ears—so easy—and then wrap the remaining fabric around your fist. Nothing to it. If done correctly, and to be honest it’s hard to mess this one up, this should look like an absolutely pitiful rabbit. Tired, beaten, weak, disheveled—the ears droop, the skin sags—and most importantly: so hungry. Yes, if it looks like years of malnourishment, you’re doing it right: the rabbit is starving, and admitting this fact is key to selling the performance. You want to be a puppeteer? Then acknowledge the needs and desires of the rabbit you have forced to be alive using only a rag. The rabbit did not ask for this. Not any of it. The rabbit just woke up here, made of garbage, in front of a crowd, or languishing in your dingy practice space, or a car, or wherever, but certainly not where it might want to be, in the safety of a grassy field, forest, or warren. No, the rabbit is lost, confused, and hungry—it cannot eat, because it’s made of cloth, and it has only fingers for organs. Knuckles for lungs? It’s like a horror movie. Imagine that the hand that made you is also somehow the very substance of your being and the thing that obstructs all your desires. Sound familiar? Great, now you’ve got the mood. So when you do the hand motion—a pinch of the forefinger toward the thumb to mimic the movement of the rabbit’s mouth—it should look like an animal that knows there’s nothing that can ever truly fill it. I believe you can do this. Maybe the hungry rabbit will pick up a penny or crumb in its mouth, sure, nice touch, but objects and experiences just pass right through it. The crumb, the penny, the laughter, the smiles, the trees, the warm embrace. The nights that stretch onward, impossibly long. They are here and then they are gone, and nothing stays, only the wind, until it’s just the cloth and the hand again, the desire and its impediment, always inseparable and slowly becoming one. The hunger. The rabbit. Hop hop, hoppity hop. Easy. And the trick, of course, is to find a way to enjoy it. To move the hungry rabbit such that we see not only its inability to hold onto anything for longer than a moment, but also the beauty it draws from each thing that is lost, like bathing in the warm exhaust from some futile combustion. But what gesture of the hand tells the story of loving an impossible hunger? Puppeteer, that’s up to you.

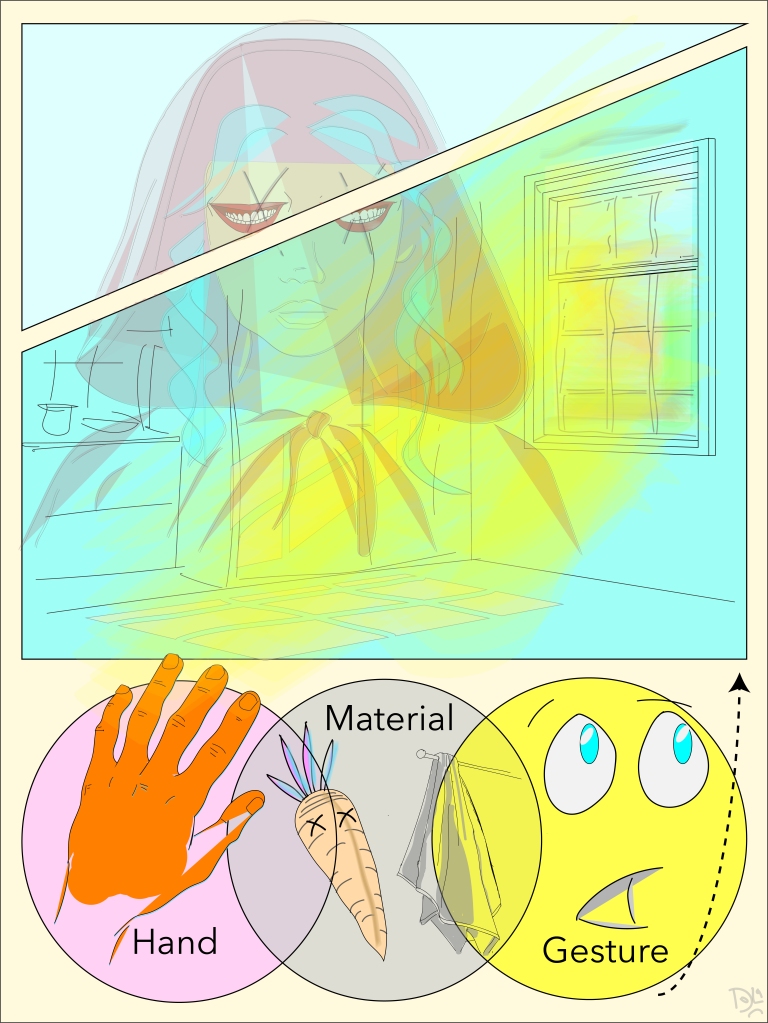

2. Little Caring Carrot (Intermediate)

Grab a large carrot you’re ready to get rid of, or any other similar root vegetable past its prime, and carve a face into the fat end—we recommend an expression of surprised delight, but any approximation of eyes and mouth will do. Wrap a rag over the top, then around the whole affair, and you’ve got the makings of Caring Carrot. Assembled correctly, with your hand under the cloth and gripping the root, this should look a bit like Little Red Riding Hood, if Little Red Riding Hood was an old moldy carrot whose face was made of crude stab marks. Perfect. All good puppets make obvious the difference between some abstract ideal and the limits of material existence, and this one succeeds, painfully so. Now we have the hand and the material, connected as intended, but what about the third element: the gesture? What motion would best animate the personality of Caring Carrot? Look into the jagged lines of its punctured eyeholes, and you will understand that what drives this carrot is a sense of innocent wonder at the newness of the world. The carrot just arrived here, it didn’t even exist just a moment ago, and unlike the Hungry Rabbit, it has no need of food, because the carrot is made of food, and so it has ample energy to consider the world and all its beauty. For the greatest effect, simply turn the carrot to face any object or scene of your choice—a clock, a table, a set of plates and silverware, patches of warm light coming through a kitchen window in the late afternoon, a group of friends laughing too loudly in another room, a collection of books, a well-worn sweater, salt and spices on a flour-dusted counter—then jostle it briefly with a quick shake of the wrist, indicating surprise, before gently letting the carrot tilt slightly upward in a curve, mimicking a swoon, a slow but genuine sense of awe and wonder that these things are real, that anything exists at all, that the carrot is lucky enough to be here and to observe it, to feel that warmth in that kitchen, to see all of these ingredients, their potential to become almost anything, cakes and roasts and soups, the pure weight of possibility, like some great blanket lain over everything, warm and comforting. Anything can happen. Yes, that’s how the hand should shake and move the carrot, just like that. But this is not the essential gesture that brings life to Caring Carrot. No, the puppeteer’s most important gesture in this case is far more subtle—because it’s not something done, but instead something undone. The key gesture is keeping secrets. Do not explain that lurking under this warm blanket of pure possibility there awaits the growl of change, and that lurking at the edge of awe is always terror. Do not tell the carrot that, while it may not be hungry because it is made of food, this is because the carrot is also slowly eating itself. Do not point out those patches of fuzzy green and white mold growing here, the dry patches crusting over there. Do not point out the part we all know has been omitted from the tale of Little Red Riding Hood; that when she arrived at her grandmother’s house and pulled back the blanket, what was hidden there in that bed was only her own reflection, an image into which she would someday be submerged and subsumed, do not admit that we’re always crawling into our own mouth, a smile burning at both ends. Yes, if you shake the carrot until none of that feels true, you’re doing it right, so keep swooning.

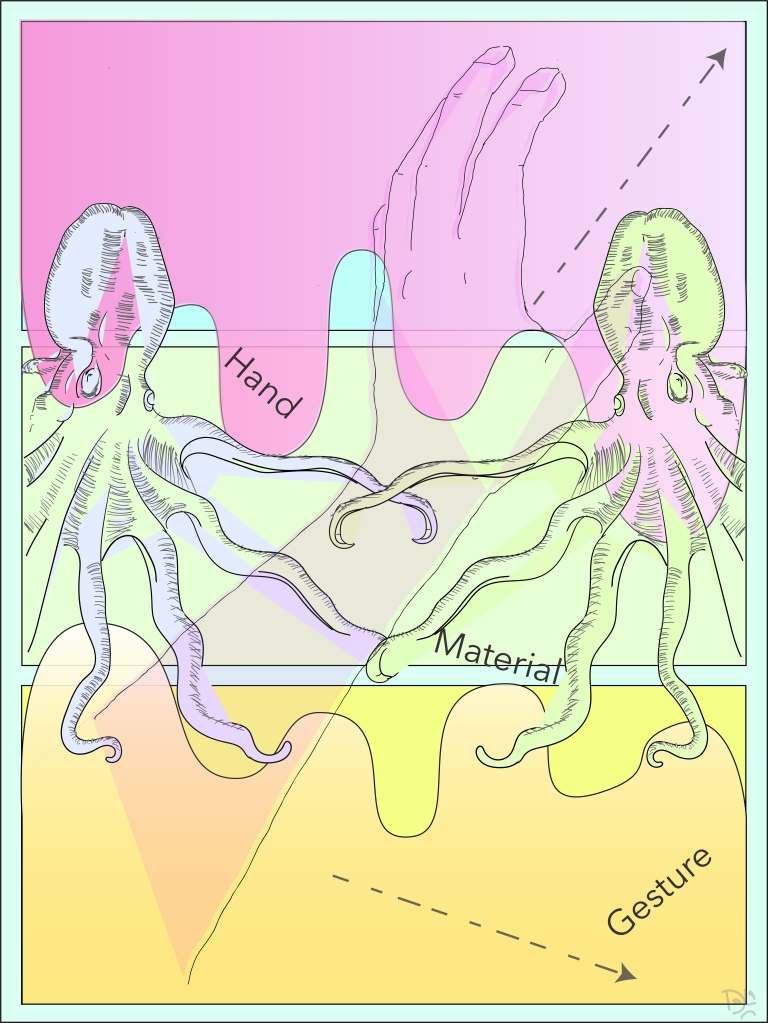

3. Sam the Social Octopus (Intermediate)

While many puppets are crafted with small and simple materials left around your home—cloth, bags, food, utensils, and other tiny trinkets—why stop there? Get creative. Slip your fingers under a lampshade and waggle it at partygoers, put your hand into a microwave and flap it around like a chubby, unwieldy bird, or open the vacuum cleaner and stuff your fist in there so you can pretend it’s a person, like it’s your friend, like it’s your loud obnoxious friend who won’t shut up, who is always around and never leaves, and who actually you kind of hate, which maybe says something about you more than anything else, at the very least that you don’t know what friendship is. Easy. Sam the Social Octopus is no different, and only requires a suitcase, ideally half-packed for a trip you abandoned and will never take. This adds character. Open the case and pull eight shirt sleeves from within, dangling them out the sides, and let them represent the long prehensile arms of the clever octopus. Next, put your own arm into the suitcase, roughly up to the elbow, and zip the whole thing closed so that, with your arm raised into the air, you wear the suitcase like a giant glove with noodly shirt sleeves waving beneath. Picture it bobbing through the ocean. Beautiful, majestic. Now we just need the perfect gesture to bring Sam the Social Octopus to life. The question then becomes: who is this sea creature, and what do they want? Like most anthropomorphized octopuses that we know nothing about and project our own feelings onto, it wants interaction and affection, friendship and love. It’s not unusual. To demonstrate these desires and bring life to the octopus, swoop the suitcase through a crowd, letting its sleeves brush the cheeks of strangers. No, actually, that’s too forward. Instead, quietly sidle the suitcase up to a group engaged in cheerful conversation, and then flick the sleeves rapidly in between them as they talk. Do it like you’re saying “hey hey hey hey.” That’ll get their attention. Or, better yet, stand in the corner, as still as possible, with eight arms limp and unmoving, just staring blankly at the people. Yes, this is how friends are made. Maybe back into the coats hanging on the door, like Homer Simpson into the bushes, or slip into the closet down the hall. Blend in. Camouflage. Yes, that’s a thing that an octopus does and so it is good that you are also doing that. In fact, an octopus doesn’t speak at all, so quit it with the small talk, too, and just hide quietly over here, conserving energy, precious energy, because every calorie counts in the unforgiving ocean of what other people think. Now, as a puppeteer, you might be feeling: why must I rely only on the hard exterior shell of this suitcase, and why must I forego the softer, more vibrant things Sam the Social Octopus has hidden inside—the pink shirts and blue pants, so much more compelling than the banality of this stiff gray suitcase and its walls. And you might be thinking, if I can just get what is inside to be outside, maybe this could all be so much easier, maybe we can show who we really are. But you’re forgetting something—the stuff inside the suitcase is only clothes, just things you wear, which is literally just more “outside,” more exterior you keep hidden away. There is no inside. It’s outside all the way down, and there’s nothing else. Puppeteer, you’re not getting out of the jar of yourself. But see that unreachable world beyond the container’s glass? You can almost touch it. Wriggle those arms like there’s still a chance. That’s entertainment. That’s jazz.

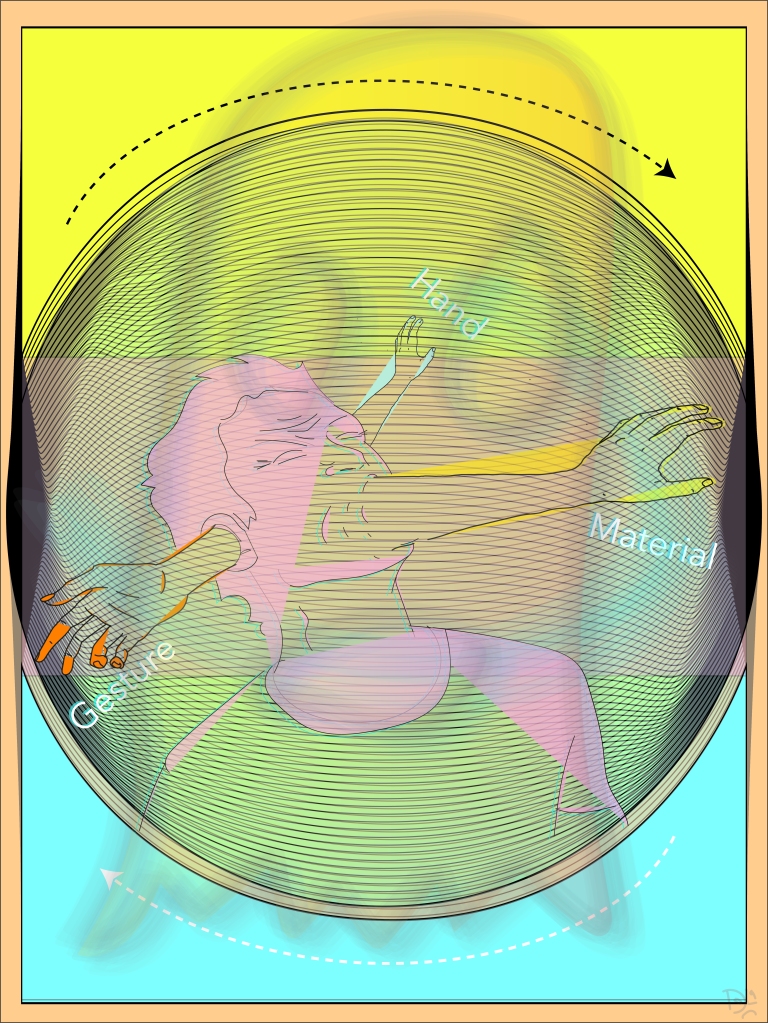

4. Haunting Hal the Dancing Ghost Bear (Advanced)

As you become more comfortable creating and operating hand puppets, you may notice that some designs ask you to put only a finger into the material, others your whole hand, and still others require a full arm, stuffed into the material well past even your elbow. But the scrupulous puppeteer may wonder: could there be more? How much further can I go? What if I put additional parts of myself into the material? A shoulder? A neck? Since a hand is something that moves through the air, manipulating the world around it through complex gestures, isn’t my entire body just one big hand? Yes, that’s correct. The space between your two hands, all of it, is just more hand. From this vantage point, whole new puppet materials open up to you, new possibilities bloom. For example, get your entire self inside a mattress and prance. Reach your fingers, then your arm, then your torso and legs into the refrigerator and shake its frame. Get into the oven and swing the door like a mouth. Now we’re cooking. Get into the car and drive. Stand inside a building and work. Be in a house and sleep. Hop in a line and wait. Establish a routine and commit. Stay there now. Let the regularity of a well apportioned day become the material into which you place your whole body. And this is how we make Haunting Hal the Dancing Ghost Bear: your complete corporeal form placed inside the rhythm of your daily life, moving around like you mean it. Do you mean it? Well, if you want to make Haunting Hal the Dancing Ghost Bear appear, then the hand is your body, the material is your life, and the gesture is to goddamn mean it already. Tell them how you feel. Hold a hand in the dark. Ask for help. Try to be with people. Learn something new. Scream into the woods. Allow the world to kiss you on the forehead, to cradle you in the embrace of small pleasures. If done correctly, the difference between yourself and Haunting Hal should become clear. Haunting Hal is the figure engaged in each of these actions—getting up, brushing its teeth, and somehow making it from one end of the day to the next, which is impossible but it happens—and you, the puppeteer, are the one who watches, the one who observes the animal figure that marches across your life. And the haunting? Well, one of you haunts the other, that’s for sure, but it’s hard to tell who, and “The great advantage of hand puppets over marionettes,” says puppet expert Richard Cummings, “is that they are truly alive—there is a living hand inside … they vibrate with life.” But wait, the curious puppeteer might begin to wonder: if my entire body is the hand in this puppet, then whose arm stretches backward from that hand of myself? This is where the expert gesture comes in: if you move Haunting Hal the Dancing Ghost Bear through your life with enough sincerity, with earnest abandon, the puppet’s own arm will emerge, reaching toward the future, and it should be obvious at this point that this arm, the ghost’s arm, is the very arm at the end of which is you, or at least the hand that is your whole body, stuffed into the material of your own life, out of which comes this puppet, which in turn reaches forward, making you, the observer and hand, who reaches into the action of your life, out of which comes the bear, the arm, the hand, the day, and on and on, each reaching into the other, looping and looping, until: who is the third who walks always beside you? This, of course, is how the dancing happens, spinning like that, hand in hand and “like you mean it.” Yes, dancing is easy, puppeteer: just pretend that you are really here.

5. The Friendly Spider, Plus Its Delicate Web and Variety Show (Advanced)

Representing the only shadow puppet in this guide, the Friendly Spider is especially easy to craft. Just follow these simple steps: 1) switch on a bright nearby light, then 2) place your hand between that luminous source and any wall, and finally 3) twist your fingers into the shape of a spider. Now waggle the tips for an impressive but unsettling effect. Wow: Just like that, and you’re already doing the Friendly Spider. Easy. But just a moment: what about the spider’s Delicate Web and Variety Show? That’s a whole different maneuver. To get it right, you’ll need to twist a lot more than your hand. In fact, you’ll need to arrange more than your whole body or even your life. To craft the spider’s delicate web and variety show, the puppeteer must orchestrate elaborate systems of power. Yes, to perform the “gesture,” one must run for political office, gain authority, achieve promotions, and generally manipulate the broad interlocking hierarchies of influence and exchange that undergird our waking lives. These too cast a shadow. Local and national governments, corporate organizational structures, and the levers of global finance; modes of production, supply chains, and social contracts: you must waggle them to impressive but unsettling effect. But how? The untrained puppeteer might imagine that by simply applying themselves, by doing the hard work, studying and getting a degree, making friends and putting in the time, they might someday waggle the tips with the best of ‘em, but this proposition is incorrect. Look around you and admit: that approach amounts to mere luck, and the actual gesture is far more nuanced. In order to grasp it, we’ll need to back up a bit and ask ourselves: in the case of any shadow puppet, what is the primary material? Is the puppet made of light? Or shadow? The answer is neither, and far more perverse: the material is the wall. Yes, of course, you realize, every puppet has some amount of light and shadow, but in the case of the friendly spider, that dial is turned up to eleven, making these elements seem almost tangible, but the hard surface of the wall is the only genuine “material” in the mix. You have to admit it. But where does that wall end? The well-trained puppeteer will observe how the wall connects with the floor and also the ceiling, and the puppeteer will note how these surfaces then stretch outward into the next room, and how each room gives way to the outside world, peeling ultimately around the curve of the Earth’s surface and back again, and thus how the wall, from this vantage point, suddenly stretches outward in one continuous plane, encompassing almost everything around you. That is the material of the spider, its web. The puppeteer will notice, too, that both light and shadow exist whether you’ve hit the switch or not, bursting from street lamps and offices, advertisements, passing cars and smartphones, or simply the sun and moon above. Dark spindles of shadow shift and stretch beneath all, little legs scampering below. The spider was already there before you ever moved a hand or waggled a finger, and it has no need of you, but skitters independent of your intention or influence. So, too, do the gears of power grind through the halls of justice without you or any one puppeteer in particular, and the long shadow cast by that lattice of interpersonal and political tumult forms the variety show, with no need of your hand-magic. And just like that, what at first seems like the most advanced of all hand puppets quickly becomes the simplest. You don’t have to do anything at all. The more you try, in fact, and the more you struggle, the worse it looks. Don’t move. Let the spider come to you, let it put you in the show. Allow the spider to move you. Feel yourself ushered from place to place by its ambivalent but relentless force. Accept that the list of things which might manipulate a puppeteer is infinite, all of the objects and processes in the world. With each breath, we draw this web in and out of us; the borders between gesture, material, and hand become ever more porous. Sure, you might imagine we retain a secret place deep within our bodies, a surface disconnected from the wall and its shadows, that we are at heart constituted by some pure thing that is discontinuous and ours alone, but no matter how many light switches we toggle, the secret wall eludes us. It eludes us because it is not there, of course. But the wise puppeteer never stops looking. Because what is not there is the one thing that cannot be taken from us. Puppeteer, keep searching for it.

Mini-interview with Dolan Morgan

HFR: Can you share a moment that has shaped you as a writer (or continues to)?

DM: The first thing that comes to mind when I think about a moment that shaped me as a writer, and that continues to shape me, is something that happened when I was very young. In early elementary school, I was obsessed with creating stories, but I could not write very well, or at all really, so my grandmother would hammer words out on a typewriter as I narrated the stories to her aloud in the kitchen of her trailer. Together, we assembled my first, uh, opus: Attack of the Pizza Munching Aliens, a kind of serialized adventure about some aliens who come to our planet to take all of our pizza. It proved pretty derivative, drawn directly from things like Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and other cartoons. In my six-year old mind, it was a collection of the coolest action spectacles I could think of, but I’ll never forget the reaction that my mom had upon reading them. At the time, my parents had just gotten divorced, I became more estranged from my father, and the stories I crafted with my grandmother all involved a father and son adventuring team. The kid and his dad braved jungles, space, and dastardly aliens, sometimes losing each other, but always finding their way back. And of course my mom, who also had the divorce on her mind, and who was greatly concerned for my wellbeing and the impact it all was having on me, saw in these stories one thing only: that I was processing my understanding of our changing family dynamics, that I longed for something out of reach. And, honestly, at the time, I was pretty annoyed by the interpretation. In my mind, I was simply writing stories that interested me, and these family details were incidental, and anyone’s insistence that something else was going on under the hood really bugged me. I didn’t like being misrepresented, and this felt like a grave misrepresentation because I had not been thinking about anything other than cool action set pieces. But with time, I’ve come to accept that we both were right, and the intersection of our two sparring conceptions of those pizza alien stories in fact sits at the center of an important element of how I approach writing to this day. That is, the subtext really was there, but I also did not intend it. Whereas my six-year old self was perturbed by that fact—the unintentional presence of meaning—I am now delighted and relieved by it. It implies that I can pursue “surface level” story tensions, plots, conceits, etc., and reliably anticipate that authentic themes will develop organically, almost without my knowing, and they merely await my discovery. This frees me to take a kind of inquiry approach to writing. I sit down with some kind of gimmick or concept in mind about what I want to put down on paper, but also with a sense of curiosity about what is going to emerge, both concretely and spiritually. I sit down as my six-year old self, but take the stance of my mother as I reflect on what emerges, trying to discover what the underlying preoccupations are with that six-year old dummy. This helps me in the editing and revision process, or in getting from the middle to the end of a piece. But it’s a great relief, to know that a kind of authentic meaning-making is always transpiring, whether I’d like it to or not, and so I don’t in any way need to force it, but instead remain open to discovering it, and thus the mystery of my own life, my day-to-day alienation from myself and sense of complete idiocy about who I am or what I am doing, suddenly becomes an asset.

HFR: What are you reading?

DM: I recently finished The Wall by Marlen Haushoffer and adored it. I can’t recommend it enough. This is a fantastic example of a story that anchors itself in concrete, physical details, but points toward numerous parallel interpretations, breathlessly even. It manages to be many things at once, and I can hardly believe that I only just learned about this book. I read The Wall immediately after having read A Short Stay in Hell, by Steven L. Peck, which I also recommend, and which makes a compelling pair with Haushoffer’s book. A Short Stay in Hell is about being trapped in an afterlife designed to resemble Borges’ Library of Babel, where the only way out is to find the book that tells the story of your life, and The Wall is about a woman trapped in the mountains by a giant invisible wall that cuts her off from all people, all of society, and the narrative of her life is transformed by these circumstances, and so they each deal with a kind of limbo space, a kind of hell or paradise, depending on how you examine each, and I am glad to have read them back to back. Likewise, another pair I recently finished: Rental Person Who Does Nothing by Shoji Morimoto and The Loneliness Files by Athena Dixon, both of which I very much enjoyed. Rental Person Who Does Nothing is a memoir, or at least a true story, about a person who does exactly what the book describes: they rent themselves out to do nothing, to whomever might need someone to do nothing with or near them. It is funny and disarming and sweet. And The Loneliness Files is a series of essays about the author’s experience with loneliness, mediated most often by a stunning analysis of the popular media they consumed while alone in their apartment. Both speak to forms of isolation, or ways of mitigating such isolation, that feel unique to contemporary life. And, now that I’m thinking about it, all four of these books are preoccupied by solitude in one way or another, and so a thematic conceit of my own reading habits, and thus my own personal preoccupations, is beginning to emerge here …

HFR: Can you tell us what prompted “Easy to Advanced Hand Puppets”?

DM: I wrote “Easy to Advanced Hand Puppets” sporadically over the span of about six months in 2023, and so it was prompted and re-prompted by an array of influences over the course of that period. The first and most obvious inspiration is the book 101 Hand Puppets: A Beginners Guide by Richard Cummings, originally written in 1962. I often like to adopt forms other than traditional story structures to shape what I am writing, and this was the underlying structural inspiration for the story “Easy to Advanced Hand Puppets.” I was given this book by my friend Simona Blat, who owns Black Spring Books in Brooklyn, and I think that moment and that space also served as a kind of inspiration or prompt for the story. I mean, quite literally in the case of being handed the book, but also the space itself, and the community there. I have had the pleasure of performing my work at Black Spring events quite often, and this piece was definitely informed by those opportunities. That is, I very much wrote each of the five sections in “Easy to Advanced Hand Puppets” specifically with an eye toward performance (which meant attempting to write each section so that it would fit into the time slot afforded for a reading, and trying to make each section do a lot in the confines of that space), and so I largely tested out the language and rhythm and tone of the piece via each of those readings. The finished product is in part prompted by the laughter and feedback of friends and audience members over the course of those six or so months. To that end, I think the community of writers I have come to know in recent years, especially the collection of poets in NYC, is therefore at least indirectly an inspiration for this piece, as they are often the reason I am able to share work at all with an audience of any kind. At the time, I was reading Impossible People by Julia Wertz, and I Meant It Once by Kate Doyle, so I think they at least unconsciously prompted some of the thinking within this story. Beyond that, I would say the work of Vilem Flusser, specifically the book Gestures, as well as Puppet by Keneth Gross, influenced the book conceptually, and Animalinside by László Krasznahorkai is a structural, rhythmic inspiration that I return to often in my work. I also love mining a cliched trope and finding a way to make it work in a way that feels fresh to me again; the icon of the puppet definitely fit that bill for me as something trite or over-utilized, which made it more fun to find my own way into it as a device. And at a personal level, I think the story is prompted by a perpetual feeling of imposter syndrome, a pervasive sense of derealization and depersonalization, the combination of which can be both demoralizing and liberating all at once; and the cloudy space between those polarized experiences is often what I like to find myself exploring in my writing, feeling along its walls in the dark to see what is waiting there for me.

HFR: What’s next? What are you working on?

DM: I’m cooking up a few new stories, a few new drawings, and a tiny musical.

HFR: Take the floor. Be political. Be fanatical. Be anything. What do you want to share?

DM: Disable the motion-smoothing function on your television, and do the same for any television on which you can get away with it.

Or just: Find something that has a direct, material impact on an issue you care about and get involved. I’m all for sharing things online, of course, because it’s important to shine a light on what matters to us, and that kind of advocacy and awareness building is necessary, but if the only thing on the car is headlights, with no wheels or engine, then we’ll only see where we want to go and never get there.

So, yes, don’t just talk about it: Disable the motion-smoothing function on your television (or, you know, any element of the world with built in settings or procedures that are ridiculous and an affront to the lives of actual living people), and then do the same for any, uh, “television” on which you can get away with it. Disabling the motion-smoothing function on your television might mean working for an organization that does that kind of thing, or putting together an event that helps raise money or materials for the people who would most benefit, or volunteering to help someone safely get where they need to go, or generally contributing some skill you have to an initiative, etc, who knows—there are a lot of ways to be a part of disabling the motion-smoothing functions on a television.

Also, if you can, take a nice, long walk as soon as possible.

Dolan Morgan is a writer and illustrator living in Greenpoint, Brooklyn, and is the author of two story collections, including That’s When the Knives Come Down. Their work has appeared or is forthcoming in BOMB Magazine, The Believer, X-RAY, The Rumpus, Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading, Selected Shorts, NPR, and elsewhere.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

Leave a comment