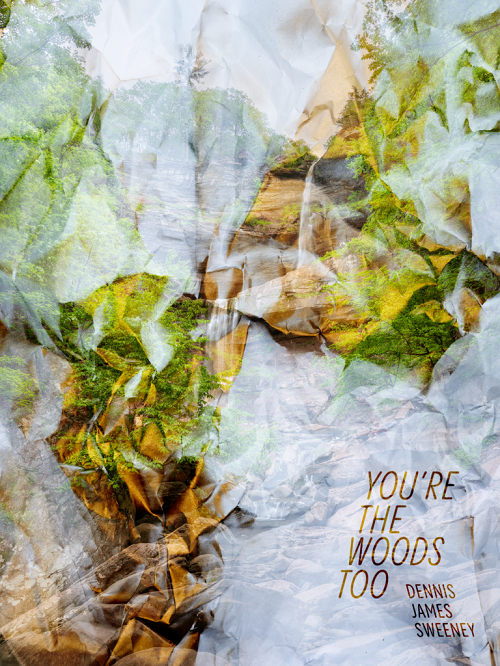

You’re the Woods Too is Dennis James Sweeney’s first full-length collection, published in 2023 by Essay Press. This hybrid collection of poems, diary entries, and prose presents Sweeney’s concerns with the experience and creation of art in solitary, natural spaces. Furthering its hybridity, the collection is loosely framed as a stage play that the authorial persona alternately participates in and flees from. Artifice and nature abound within the pages of the collection, as stage drama butts up against confessional, and perhaps autobiographical, diary entries. Sweeney uses these mixed media—filled with humor, surreal pseudo-dreams, and a deep sense of loneliness—to probe into aesthetic and philosophical questions of presence versus absence and art versus life. Sweeney is already in the know, though, that the false binaries, often erected between the categories he traffics in—nature vs culture, art vs environment—use topics and ideas that are deeply intermeshed with, and inextricable from, one another. In this way, You’re the Woods Too nicely marries form and content, using mixed poetic and prose forms to embody the complexity of Sweeney’s poetic vision.

Throughout You’re the Woods Too, Sweeney questions the value of art when it interrupts human relationships and displaces community. In the bulk of the narrative sections—a series of journal entries made while Sweeney spent several days in the Oregon wilderness at Shotpouch Cabin—the poet ponders the benefits of solitude to his writing practice but finds that it isolates him from his female companion, S., who frequently distracts him from his writing. The tension between writing in solitude and existing in community haunts Sweeney throughout the collection. As Sweeney observes in multiple poems, he retreats from human contact to engage in artistic expression but, ironically, having arrived at a place of nature and absence, he desires the presence of human engagement. In the entry “Petals/Hearted/House // Day 4, Morning,” Sweeney writes:

Just like that—the frogs stop barking.

It had to be this way: Otis Redding. The leftover salad. Quesadillas with cylinders of chicken. …

In other words, a fight.

Over poetry, but really over one loving the other more than the other loves the one, or so our story goes. Your lines have room for me. My lines are always running from you.

Otis hides in the woodwork.

These diary entries—doctored and artificial though they may be—contain moments of lyrical intimacy that draw us in to domestic spaces. Lyric intensity abounds. In an early entry (“Mice/Holy/Camera // Day 2, Afternoon”), Sweeney writes:

We go on a marshy walk and we consider the blue light our galaxy is bathed in and, as the only life that can do it, whether to punt a flowerhead off its stem. Mostly, though: are there mountain lions here?

The rocks around the firepit are heavy, and I’m not even carrying them.

…

With this emptiness, I only want to make more empty. History would laugh if I said there was nothing in the woods to respond to, but why respond to trees?

These charmingly quotidian moments reveal the mundane moments—moving rocks, worrying about predatory wildlife—that accompany even the most high-minded woodland excursion.

In counterpoint to lyrical entries, replete with interpersonal drama and natural sublimity, the collection includes roughly two dozen short poems, all of which begin with the scientific name of a species of moss. One of the moss poems, Rhytidium rugosum (which a quick Google search reveals to be the Golden glade-mist), reads, in its entirety:

Boredom reaps

Its enemy

The casual

Casual

(Blink blink)

A train tears through a car like an animal

We invent a cruel, imaginative God

These small poems provide a respite from the book’s long-lined, densely meditative narrative-driven sections. Moss poems also serve as minimalist distillations of the collection’s major concerns, refining Sweeney’s concerns with presence, absence, the ecological world, and human community into terse, minimal lines. Were we to assume that the scientific names presented before each moss poem were an attribution rather than a title, the poems could be read as incorporating language directly from mossy inhabitants of the Oregon ecosystem. In these poems, Sweeney reveals the influence of Lorine Niedecker, whose poems of place and isolation undergird much of You’re the Woods Too.

In addition to Niedecker, Sweeney draws on the—admittedly bloated—tradition of male American writers who seek solace and solitude in the forest, placing Henry David Thoreau (who Sweeney never names but clearly alludes to) at their forefront. Sweeney begins many sections—all opening with a hanging indent before shifting to sequences of short, punchy prose poems—with Thoreau’s famous words “I went out in the woods to find ….” These sections, and Sweeney’s writing in general, are highly self-aware and problematize the privilege and gendered exclusivity present in the male-dominated tradition of solitary nature writing. In a section of the stage play set early in the collection, Sweeney invokes the satirical LONG LINE OF MEN who he symbolically joins in his poetic sojourn into the wilderness. Following a dramatized hike which takes the hikers along “a knife ledge above a scree field,” Sweeney poses the rhetorical question:

When WE return from the woods, have WE changed?

And who tells the stories? It is a LONG LINE OF MEN.

They walk on stage with hope or suspicion, dejected or wearing a shrewd grin … But each member of the LONG LINE OF MEN walks offstage after his monologue with the same mix of pleasure and bewilderment.

The MEN want to live without anyone. They leave to seek that place where no one is.

Yet Sweeney’s feelings are genuine—even if they are not unique—and his love of nature is sincere, despite the discomfort, felt by reader and poet alike, of the patriarchal forebearers lurking in the background.

Sweeney’s powerful debut collection is timely in its ecological concerns and its formal experimentation, and the lingering questions that the book asks are aesthetic as well as philosophical. Sweeney is concerned with the ethics and aesthetics of retreat, asking what place there is for an individual, a couple, or a hypothetical family in a space of so-called natural emptiness. Is self-isolation too great of a price to pay for art? The collection provides no answer but shows that, as Sweeney poignantly writes:

The problem is that when I retreat from the world, I also retreat from myself.

Where am I when I go out in the woods? Gone.

You’re the Woods Too, by Dennis James Sweeney. Buffalo, New York: Essay Press, May 2023. 132 pages. $18.00, paper.

Connor Fisher is the author of A Renaissance with Eyelids (Schism Press, forthcoming 2024), The Isotope of I (Schism Press, 2021) and three poetry and hybrid chapbooks including Speculative Geography (Greying Ghost Press, 2022). He has an MFA from the University of Colorado at Boulder and a Ph.D. in Creative Writing and English from the University of Georgia. His writing has appeared in journals including Denver Quarterly, Random Sample Review, Tammy, Tiger Moth Review, and Clade Song. He currently lives and teaches in northern Mississippi.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

Leave a comment