There is something powerful about newness, when you first hold the book in your hands, its glossy cover and particular weight. Release parties, the words of praise on the back, honest or not. Newness is a vulnerable state. The artist has sent it onto the world and the world has yet to decide if it needs the work. A conversation either begins, or it doesn’t: new inspirations bloom from it, or the public moves on.

Some books refuse to be passed over. Bestsellers will go on to have reprints, be on lists, maybe win an award, someone at a major house is meeting with someone else, a new edition, an anniversary. They hit that magic mixture of quality writing, shaking the right hand, and timing the zeitgeist. Others refuse to be done because their purposes did not live entirely on the page. You find this in the grassroots genre of poetry today, where self-publishing, conversation, community engagement are not only necessary, but for many, they are the preferred method of sharing text. Poetry is meant to be performed, seen live, it is meant to be interpreted, contorted, reflective, multi-conscious.

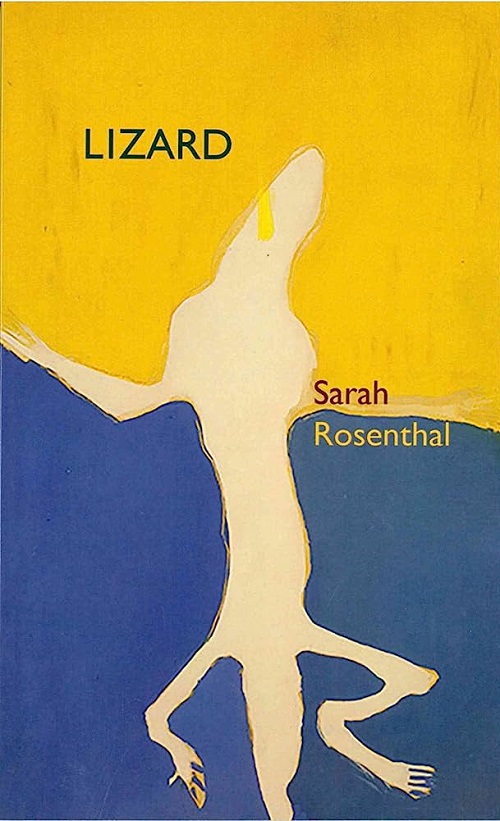

Sarah Rosenthal’s 2016 collection of poems, Lizard, is one of these collections that continues to thrive today not only because it is a terse volume of well-composed brevity, but because its purpose was and is not limited to what’s between the covers. You can expect this from the author of A Community Writing Itself, a poet who knows how to spot the vanguard, and engage with it. Poet, critic, teacher, life coach, and now film producer, the author of Lizard fills many roles, and her text has many lives.

When I received a review copy of the book in 2016 I was entering into a doctorate program and my second child had just been born. I did not know how much time I would have to devote to the text: worrying that new is better, and anything I wrote would be long delayed. It turned out that my reticence was founded because I could not engage with the book the way that it deserved, regardless it stayed with me, feeling like unfinished business. Not out of any sense of obligation, but because the poems refused to unlatch themselves from my mind. When I returned to the work of considering this text, I was again met with its multitudinousness. It begins with L. Who is L? She moves back and forth; we dreamed her and became her in that moment when our name was called and we turned toward the voice but it was someone else being spoken to.

“Lizard,” a character, appears in the first poem: “I don’t share your / brain.”

“L,” a character, appears in the third: “replaceable / parts help L stay / cutting edge.”

And “poet,” in the final poem: “mostly we’re not / original wrote the / poet and L agrees.”

They are most of the time distinct, but intertwined. This distinction is a kind of lead-in, easing us into the subjects. There are hints thrown in (for example the book is dedicated to a “Liesl”) but, as opposed to playing detective, allowing the fourth wall to remain intact is an enjoyable way to observe the text. Lizard is an endangered, damaged, but resourceful and creative creature. A creature of determination:

Lizard bakes

on asphalt. A

car might crush

or maim her. Dear

God, she writes,

why have I lost

capacity, learned

pain?

Moving through the urban, this creature struggles to make herself. That making of the self is a central point of the text, at its core the concept of fluidity. The self is not a single thing, parts can be replaced. We know, of course, of shedding one’s tail as a defense mechanism, the uniqueness of these reptilian amputations is their liminality. Amphibians share a lateral-line which replaces neuromasts after amputation. While it is not entirely understood, and understudied, new neuromasts are formed from the most distal bud, forming a migratory cell mass. Likely a combination of the most common forms of cell replication; mitosis and transdifferentiation, one becoming two, or one spontaneously becoming another. L speaks all of these languages even if, like us, none of them are fully understood. We see her turn her belly up in self-defense, and in pleasure. We see Lizard doing human things like waking groggily in the morning and having bad breath. We see her doing lizard things: “She / regulates. Revises / her heat to match / the universe. Seeks / agreement.” We see her blending the scaled with the incredible as well, seeing through the emperor’s clothes:

Mostly eats the living.

On account of her

eyes. They see what

moves. She stalks

the world nude, I

want to say reveals

the world’s nudity.

Want to say we’re

all that emperor.

That lonely thing

with mirrors

Throughout the collection, the poems play within the temptation to define this series of morphologies. Enjoyment begets the turning of this kaleidoscope of characters in the hands and I admire that the shape refuses to settle itself down. L plays in the freedom and anonymity from any kind of self that doesn’t fit the present. That satisfaction that comes from getting away with something risqué; the feeling one has when one reads a poem, or has a beer with lunch on a workday. But it’s something more than that, as one builds themself, they build and change their environment as well. These poems contain a lyrical playfulness that delivers awareness of escaping something that could have caused injury; when luck and skill in equal measure help the body to avoid a set of stitches, or a definition that doesn’t agree with the self. The poem is a kind of acrobatics. Concocting Lizard took a discipline and self-restraint that is endearing of athletic practice while hinting at a born-with-it prowess. “Far / enough into the / moment you’re / timeless.”

Lizard enacts, rather than suggests, and it is in that thesis it has found its second life:

you’ve been waiting

for a lizard to topple

you, now it happens,

now go build a frame

for the raw moment

“Build a frame for the raw moment” is as much this collection’s self-prescription as it is its call to action. In 2020, the book’s author collaborated on a short film, We Agree on the Sun; while this was an independent work, it is thematically congruent with Lizard. View a trailer here:

Currently the book is continuing to inspire performance art: a series of five songs were composed based on the poems found in Lizard, and which inspired dance choreography. These artistic inspirations have come together in a film titled Lizard Song Cycle which is currently in development. A film is another thing altogether; for every one person involved in the creation of a printed text, which is itself a small miracle, there are three people tapped to produce its screen adaptation. For a project that was born, and remains largely grassroots, the production of a film stresses the limits. Given the discipline and acrobatics of the text I am excited to see where this book will find its next life on the screen.

As time went on I wondered if this second life that the book had found was not baked-into the text, but born out of it, or both. There is evidence that the book’s prescription “build a frame for the raw moment,” began its enactment before the text was even completed:

I forgot poems for

a reading. I had one,

filled with typos.

luckily the hostess

had a copy of the

Lizard manuscript.

Do you like it, a

question I never

Ask. She laughed.

If we are to believe the narrative, and Rosenthal’s praxis leads us to do so, then this is a text that has been engaging, not only with the performative aspects of its genre, but also the communal aspects before its completion. Performance is its skeleton, its larger community is its scales.

Lizard, by Sarah Rosenthal. Tucson, Arizona: Chax Press, June 2016. 75 pages. $17.00, paper.

Alex Rieser is the author of the chapbook Emancipator (New Fraktur Press, 2011), and has internationally published poetry, fiction, interviews, and criticism. His work has appeared in Ploughshares, The Cossack Review, The Portland Review, Paris Magazine, The Prague Review, and many others. He holds an MFA from the University of San Francisco, where he served as Chief Art & Poetry editor for Switchback. He currently lives in Riverside, California, with his wife and son. More at alexrieser.com.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

Leave a comment