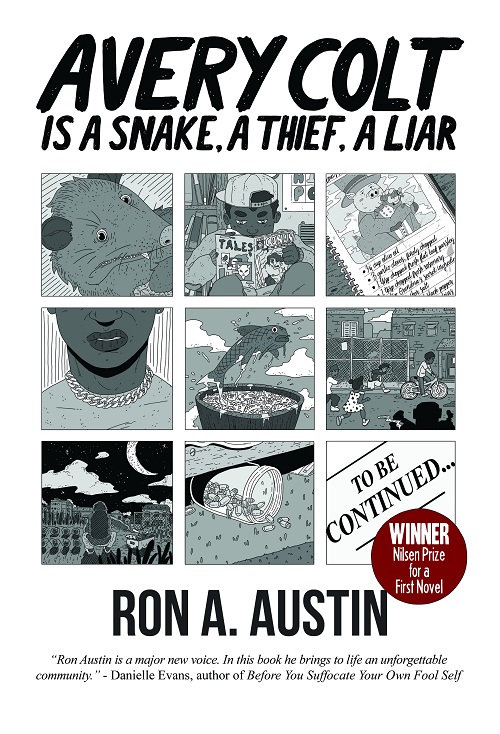

Avery Colt is a kid who could use a break. In addition to the everyday struggles of adolescence, he’s caught in the webs of poverty, masculine expectation, and systemic racism that are keeping him, his family, and his community down. Set in North St. Louis, Ron A. Austin’s debut novel (winner of the Nilsen Prize) follows Avery Colt from nine-years-old through the beginning of manhood. Although he regards being “soft as pudding” as his downfall, it might actually be his saving grace.

The structure of this book works in its favor. It’s told as a novel-in-stories, and within each story, the reader sees Avery struggle with a new adult insight or expectation, or maybe just the realization there are things he won’t understand, that adulthood is not going to hand out all the answers. He learns about desperation, self-reliance, the power of relief, and the power of pain. Within the novel there are also notes passed among the characters, a to-do list of man’s work (killing rodents, slaying goats, and setting people straight), a recipe, and an equation for the perfect daughter—all clues and tokens for Avery to piece together the world of “Grown Folks Business.”

The book opens with an article that ran on October 21, 1983 in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch about a shop owner who shot two armed youths trying to rob his store, and while I can’t say for sure Austin has direct experience with those people, his authority regarding the place and characters is stunning. Each sentence is an immersion in this specific Midwestern experience, down to the flavor and toil of the language. As he writes:

The dialect I spoke at ten years old was three licks neighborhood slang, two licks swear words Mom and Dad used when no one important was listening, and one lick southern drawl I gleaned from neighborhood elders gossiping on brick porches. That chop-shop dialect coated my throat like mucous, muffled my vowel sounds, made all my consonants roll lazily off my tongue. I loved that Midwest slang.

Just as Avery is figuring out the formula for his speech, he’s trying to figure the formula for existing in this world. As much as he wants to be someone else, someone easier, he is who he is: a boy constantly coming up against what he sees as his failures. He’s unable to drown a possum in the toilet because he’s not tough enough; he feels guilty about taking part in the robbery of a beaten man when others saw it as something to brag about. His very failures are what make his moral core, but what do you do when that just makes life difficult? He says:

If I was a different kid, I would have taken off my shirt and joined D, braying No lie, me and that cold-blooded nigga Big D, we whopped that bitch-made nigga—Wham! Wham! Wow—brains on the motherfucking pavement. But that wasn’t me. I turned and biked through traffic, D’s shouting like stones pelting my dusty side. If a monster truck had hit me, splattered me under sixty-six-inch tires, I wouldn’t have been sorry. Not at all.

Threaded through this is an adult Avery looking back, making sense of his life and what he learned growing up. In the same story that lists a man’s responsibilities, he realizes, “I couldn’t articulate it back then, but I was beginning to learn how anxiety could hijack the circuitry in my brain and redraw the world in wobbling, surreal lines.” Yet diving further, later in the story, he captures how well that anxiety can be mixed with nostalgia, a sense of place, and a child’s remembered voice:

Folks loved the corner store. But I used to hate it so bad. Granddad and Grandma always put me to work sweeping ashes out of the smoker, washing grit out of collard greens, sponging pig’s blood off the butcher’s table. I didn’t understand that years later, after the corner store was nothing but weeds and rubble, I’d still smell ancient charcoal smoke on my skin, feel grit under my fingernails, see my palms stained with blood, and succumb to a crippling grief, the kind that closes over you like wings, eclipses the best days.

At its heart, this is a book about family and community: Avery’s namesake who was caught up in the drug trade, his grandmother and her recipes that can’t be duplicated by ingredients alone, a grandad known “for handing out good, country ass-whoopings,” and a mother and sister who fight so hard only a soft son could bring them together. These characters all shape Avery into the man he will become through tough lessons complicated in the learning.

Avery Colt is a Snake, a Thief, a Liar, by Ron A. Austin. Cape Girardeau, Missouri: Southeast Missouri State University Press, October 2019. 172 pages. $18.00, paper.

Erin Flanagan is the author of two short story collections published by the University of Nebraska Press: The Usual Mistakes and It’s Not Going to Kill You, and Other Stories. She is an English professor at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

Leave a comment