David Foster Wallace once said, “Art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable.” Art in all its forms serves to disrupt. Yet, there stands a difference between the grotesque and the garish, the disturbing and the obscene, art and invasion.

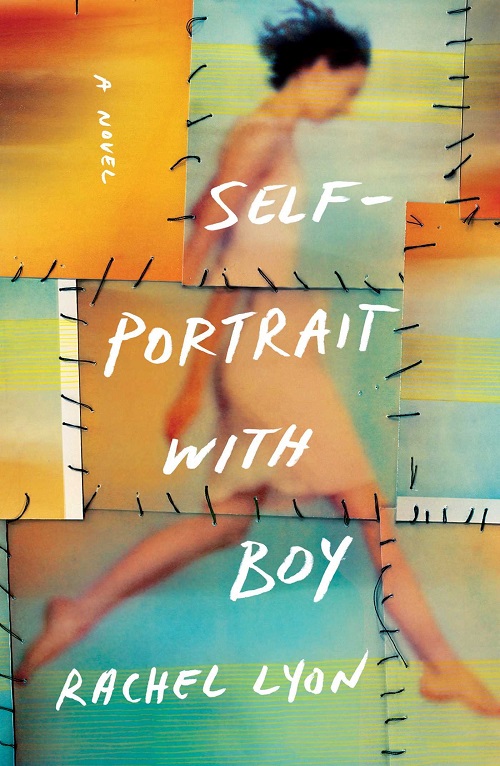

This is the premise to Rachel Lyon’s debut novel, Self-Portrait with Boy. The main character, Lu Rile, aspiring artist, “a skinny friendless woman in thick glasses with a mop of coarse black hair,” is one day faced with a photo that can either propel or shatter her career as an artist, and she must decide whether to share it with the world, or even if she can. She has captured her masterpiece, and it just so happens to be the image of a young boy falling to his death. Not fallen, falling. Caught in the act, his final seconds of life.

Self-Portrait with Boy is an edgy, vicious tale. This debut hooks its readers quickly. This is a story told with succinct prose and pithy dialogue, the reader openly addressed by an older, if not wiser, Lu looking back to when she was “twenty-six, naïve, and ambitious as hell.” Lu speaks with a self-effacing, conflicted voice, a voice indistinguishable as remorseful or simply resigned. “I’ll tell you how it started,” the book begins:

With a simple, tragic accident. The click of a shutter and a grown man’s beast-like howl. The silent rush of neighbors down our dark dirty stairs. The lights of a police car illuminating the brick wall behind our building. And a photograph.

I never meant for any of it to happen.

The young boy from the apartment above has fallen from the roof to his death, and Lu is there to capture his fall on film. Self-Portrait with Boy is Lu’s account of the aftermath and her own role in it, narrated years following the initial events. Lyon sets up the perfect storm of ambition and desperation brewing in our young narrator. Lu lives a mediocre life, immersed in struggle—to keep the boiler running through the bitter New York winters, to keep her camera full of film, to keep working and creating so as to fill her long days with any purpose. And then Lyon delivers the final, swift kick that sets it all into motion: a chance for a better life. Lu simply cannot resist.

What began as an accident soon spins out of control. The young boy’s death takes on new life and creates a new life for this starving artist. As much as by chance and by direct result of Lu’s dedication to her art, the photograph of her lifetime falls into her lap, or rather past her window, and she cannot help but share it with the world. She describes the photograph as such: “Heartbreaking. Cruel. Fresh. Real. This photo could change everything, I thought. (…) It could transform me from the unknown photographer I was into the artist I wanted to be. (…) I was hungry with anticipation. Self-Portrait #400 could change my life.” And it does.

Lu goes from unknown grocery store clerk fresh out of art school to front-and-center new initiate into the cutthroat New York art scene, wielding her Self-Portrait #400 like a torch lighting her way to fame. All while slowly building a relationship, a friendship with the boy’s grieving mother, Kate, who lives just overhead. “The thing you have to understand, the thing you have to keep in mind, is that Kate was my friend,” Lu says. “At the time she was my only friend. She was so dear to me.” The two women cling to one another, using, needing, the other to quell the loneliness they each feel inside, though the roots of their loneliness stem from such different sources. Lu seeks asylum in the inner sanctum of Kate’s friendship, recognizing in her another lonely soul so like Lu’s own. And then she turns around, taking that grief, spinning from it profit, gaining from everything Kate has lost.

Why, we ask, does Lu do it—why did she take a photograph she knew should not be shared and bring it out into the light? The photograph happened by chance, yes, but what she does with it is plotted. Intentional. The tolls Lu’s ambition take on this friendship are so staggering one cannot help but wonder how it was not, somehow, anticipated. Her ambition and drive for fame come at increasingly high costs as the novel unfolds, and the reader is helpless to turn away, so well-crafted are the depictions.

Lyon has created a brilliant, dynamic work with Self-Portrait with Boy, exploring the depths of human desperation on so many fronts: The desperation of the young to make their marks, to show they are worthy, to show that they exist. The desperation of a grieving family torn apart by the death of their son. The desperation of the world to catch a glimpse of the tragic, the obscene, even when we know better than to look.

The tell of great literature is that the people on the page really do feel, think, and act human. We might pull away from Lu with revile, turn from this story reeling with how it all ends, but what we secretly revile so much is Lyon’s expert way of showing us yet another self-portrait we do not want to see. This time, her lens has been turned toward the readers. We can stand and point fingers at what Lu did, but we have to ask ourselves, what would we have done? I don’t know many among us who would not have followed in Lu’s footsteps. The characters’ actions, damning though they were, were not unjustifiable within the context of the story. It is not always enough just to have created, we must realize, but to be recognized as the creator. With her debut, Self-Portrait with Boy, Lyon has created something as unique, compelling, and exquisite as it is terrifying, and she is certainly being recognized for it.

Self-Portrait with Boy, by Rachel Lyon. New York, New York: Simon & Schuster, February 2018. 384 pages. $26.00, hardcover.

Paige M. Ferro is Deputy Editor at Alternating Current Press. Her fiction has appeared in Foliate Oak Literary Magazine, Rose Red Review, and Lit.cat. She holds degrees in Creative Writing, Literature, and Spanish from the University of Montana, and her writings focus on Queer Studies. By day she is the Adult Programs Coordinator for Deschutes Public Library in Bend, Oregon. You can find her online at PaigeFerro.com or on Twitter or Instagram at @Ferro3Paige.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

Leave a comment