Kelly Link’s fiction follows the same kind of logic that lets you coast through a dream where your partner is played by your tenth-grade math teacher and you’re wearing roller skates, yet there doesn’t seem anything weird about it. In Link’s stories, mermaids are an invasive species, the job of superhero sidekick includes a lot of paperwork and flesh-pressing, and sleepers and shadows and alcoholism and support groups are equally “part of the weirdness.” Yet all of it somehow viscerally makes sense. These stories open like magical boxes that keep opening to other boxes, or as Link writes in “Secret Identity,” “Inside this game, they were playing a game.” Each perfectly encapsulated reality here is a game within a game, a metaphor within an object, a dream within a reality, a story within a story.

Often categorized as slipstream, Link’s fiction embraces the strange, but what’s interesting is how un-strange it can feel to a contemporary reader. As Sherry Vint has said in “Symposium on Slipstream,” when the term “slipstream” was coined by Bruce Sterling in 1989, it might have seemed odd, but “in the twenty-odd years since Sterling coined the term, the times have ceased to feel as strange; indeed, for many the cognitive dissonance, questioning of consensus reality, shifts in point of view or setting, and denial of narrative resolution that have been deemed characteristic of slipstream remain signs of how we feel, but this feeling is now familiar rather than strange.”

Part of what makes Link’s slipstream so un-slippery is how grounded the stories are in details and objects. Take the monkey egg in “The Summer People”:

She wound the filigreed dial and set the egg on the floor. The toy vibrated ferociously. Two pincerlike legs and a scorpion tail made of figured brass shot out of the bottom hemisphere, and the egg wobbled on the legs in one direction and then another, the articulated tail curling and lashing. Portholes on either side of the top hemisphere opened and two arms wriggled out and reached up, rapping at the dome of the egg until that, too, cracked open with a click. A monkey’s head, wearing the egg dome like a hat, popped out. Its mouth open and closed in ecstatic chatter, red garnet eyes rolling, arms describing wider and wider circles in the air until the clockwork ran down and all of its extremities whipped back into the egg again.

There is no questioning what the monkey egg looks like and sounds like as it nearly materializes in the reader’s hand, but what it portends, Link invites the reader to interpret. Like the whore-igami one of the characters is making, a literalized metaphor, shapes come to life: “Men and women and men and men and women and women in every possible combination, doing things that ought to be erotic. But they aren’t; they’re menacing instead. Maybe it’s the straight lines.” Everything is crystal clear, drawn with straight lines and twenty-six letters, but nothing is quite what the reader is expecting, like the child’s toy turned threat.

The stories’ odd worlds—occupied by demon lovers, superheroes, ghosts, and wedding guests—are both the point and beside the point, mere backdrops to the very real human struggles among good, evil, jealousy, and desire. These worlds do more than set up the stories; they seem to point to the weirdness of the world we actually live in. Here’s a description of the world in “Light,” for instance, told in the “calm, jokey pronouncements of the local weather witch”:

The vice president was under investigation; evidence suggested a series of secret dealings with malign spirits. A woman had given birth to half a dozen rabbits. A local gas station had been robbed by invisible men. Some cult had thrown all the infidels out of a popular pocket universe. Nothing new, in other words. The sky was falling. US 1 was bumper to bumper all the way to Plantation Key.

It seems both recognizable and foreign, both like where we live and not like it at all. And as for the pocket universes:

Some had been abandoned a long time ago. Some were inhabited. Some weren’t friendly. Some pocket universes contained their own pocket universes. You could go a long ways in and never come out again. You could start your own country out there and do whatever you liked, and yet most of the people Lindsey knew, herself included, had never done anything more adventuresome than go for a week to some place where the food and the air and the landscape seemed like something out of a book you’d read as a child; a brochure; a dream.

And maybe that last line is Link’s stories in a nutshell. Or not. Trying to define them seems to miss the point, but one can say that in many ways, this is the best kind of collection a reader could hope for: one that continually niggles at the brain and emotions, luring you to keep playing the games within the games, to find the reality within the unreality, the truth within the fiction, and as with any good dream, you don’t want it to end.

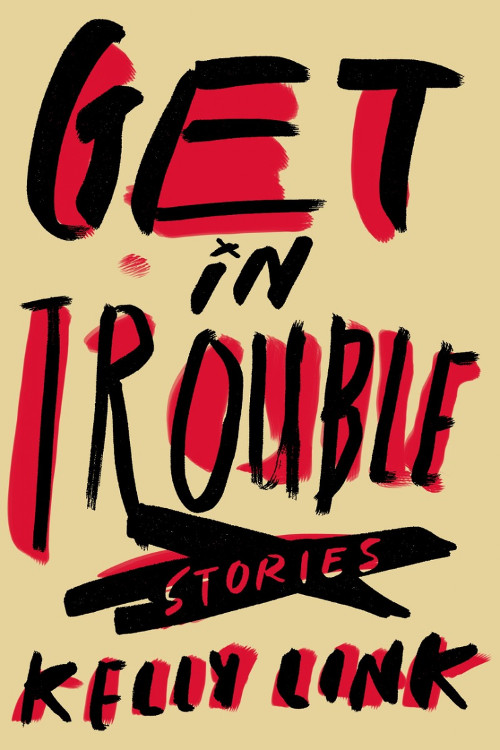

Get In Trouble, by Kelly Link. New York, New York: Random House, February 2015. 352 pages. $25.00, hardcover.

Erin Flanagan is the author of two short story collections published by the University of Nebraska Press: The Usual Mistakes (2005) and It’s Not Going to Kill You, and Other Stories (2013). Her fiction has appeared in Prairie Schooner, Colorado Review, The Missouri Review, The Connecticut Review, the Best New American Voices anthology series, and elsewhere. She’s held fellowships to Yaddo, The MacDowell Colony, the Sewanee and Bread Loaf Writers’ conferences, and this summer served as faculty at the Antioch Writers’ Workshop.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

Leave a comment