Lana Del Rey is a smart artist, a self-styled “gangster Nancy Sinatra.” She references Whitman, Plath, the Beats; wears and sings about heart-shaped sunglass as though she herself is a vintage cover (sonically, visually, textually) of Lolita. But it’s really only on her unreleased songs that she also sings about the murderous dark side of the Lolita equation:

Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul.

Just as for Lolita, fire and sin overwhelm life and soul for Lana Del Rey on her unreleased work, via many outward references, masks, and gestures towards a style of invented “self.” It is in this unreleased work that the far reaches of her many cultural and literary references are explored and in this sense, she becomes a sort of sonic Cindy Sherman, unbound and engaged in frequent anachronism. In many of these songs, Del Rey is out of time and seems out of her mind, as she frequently reminds us through the limit of a pop track. As she intones repeatedly in “Serial Killer,” her voice like sugar on organ tissue, “Baby, I’m a sociopath.”

I suppose this doesn’t totally sound like Del Rey from Born to Die, Paradise or especially the most recent Ultraviolence in which a more traditional exchange is enacted with the love object. In these albums we recognize a liberating pattern most often associated with a hit like “Blue Jeans” or “Old Money” and the portrayal of a melancholy, ultimately conventional reciprocity with a boyfriend is established (or frustrated) because of death or distance, Wuthering Heights-style. I find the unreleased songs of Lana Del Rey most interesting[1] because the Unreleased Del Rey creates a sort of poetics of intensely feminine, concentrated romantic energy which channels meridians of the “Money, Power, Glory” Del Rey incants in the same-titled track:

You talk lots about God

Freedom comes from the call

But that’s not what this bitch wants

Not what I want at all

I want money, power and glory

I want money and all your power, all your glory

Hallelujah, I wanna take you for all that you got

While we can hear Del Rey’s relentless desire and facility to tap the vein of the (always) male, (often) corporate and (sometimes) religious or otherwise domestically engaged on her released albums, what I really adore about Unreleased Lana Del Rey is how intensely explicit the tracks become regarding the way she will satisfy her cravings. It isn’t Del Rey’s actual desires I’m gripped with (a lot has been written about her personal transparency regarding addiction, suicide, and death); rather it’s how she seizes them, then proceeds to function in parallel through a multiplicity of personas.

Fascinating aspects of Del Rey’s songs “Prom Song (Gone Wrong)” and “Jealous Girl” are their access to cults of female ritual that channel the work into established traditions (both lyrically and sonically) which harness the grouped energy of cheerleading and the prom ceremony to gain velocity. It isn’t the ritual itself that has gone wrong in these songs—Del Rey appreciates, validates Americana, and seems not to transform but rather to join and transcend its iconology and ceremony[2]—rather, it is the ritual itself which is used for wrong. Del Rey is the Bad Priestess, the Noir Goddess, the Cheer Captain, The Fucking Prom Queen: never acted upon, always acting. Often what this means for Del Rey, however, is an ultraviolence against the love object. Take these lines from “Jealous Girl” (the ultimate cheerleader anthem):

Baby, I’m a gangsta too and it takes two to tango

You don’t wanna’ dance with me, dance with me

Honey, I’m in love with you

If you don’t feel the same,

Boy, you don’t wanna’ mess with me, mess with me

(Why ’cause I’m a)

I’m a jealous, jealous, jealous girl

If I can’t have you baby, if I can’t have you baby

Jealous, jealous, jealous girl

If I can’t have you baby, no one else in this world can

BE AGGRESSIVE

B-E AGGRESSIVE

The friction between the cheer chant and the blatant inversion of the romantic pop sentiment creates quick fire in this track. Lyrically, I was originally interested in the way this song weaponized “love” as it is often accepted in the pop ballad, pointed out in a seemingly ironic fashion through the persona of the cheer captain that possession, jealousy, and the structures of romantic sentiment that many Top 40 hits accept as their architecture are in fact a base of violence and instability. However, the voltage created in the slippery, tonally unknowable space where an instance of irony occurs can often be the action that sends electricity in multiple directions. Upon many listenings, I have become fascinated with the moment this songs breaks into the cheer chant because it embraces a fused and dynamic force through the use of an an ironic base. In its final minute the song incorporates a stomping, chanting, ritualistic verve of words and movement always learned over time within a community of dedicated athletes. I find it just as difficult to suggest that this final moment and its command to “B-E AGGRESSIVE” is ironic as I would to suggest that a high-flyer’s backflip off a twelve-girl pyramid is ironic, or that Dickinson’s expulsive “I’m nobody!” is ironic. I suppose I mean the line that ends in an explanation point can also be genuine.

I think the poetics of the Unreleased Del Rey’s is in these strata of equally genuine yet unachievably integrated persona: of mask upon a mask upon a mask composed of violence, critique, and a performance of sincerity. But how does one “perform” “sincerity”? How does one “act” “genuine”? Again, I think of Cindy Sherman in the terrific largess of her Untitled Film Stills, which through their capacity to reveal the “true” “her” “self” in every photo only, in concert with all the other photos, prove not to say that woman is a multi-faceted, byzantine beauty composed of genuine layer atop genuine layer, but rather through the impossibility of jiving each of Sherman’s layers with the other that there simply is no genuine “self” to Cindy Sherman. None the viewer is granted access to anyway.

Perhaps refusal of direct access is the reason why I keep thinking about apparatus theory and the following words from “Images of ‘Women’: Judith Williamson Introduces the Photography of Cindy Sherman,” a meditation written in 1983, when I hear Lana Del Rey intone about cherry Coca Cola, heart-shaped sunglasses, and white bikini tops in 2014:

Sherman’s pictures force upon the viewer that elision of image and identity which women experience all the time: as if the sexy black dress made you be a femme fatale, whereas “femme fatale” is, precisely, an image; it needs the viewer to function at all. It’s also just one splinter of the mirror, broken off from, for example, “nice girl” or “mother”. Cindy Sherman stretches this phenomenon in two directions at once—which makes tension and shapes her work. Within each image, far from deconstruction the elision and image of identity, she smartly leads the viewer to construct it but by presenting a whole lexicon of feminine identities, all of them played by “her” … In Untitled Film Stills we are constantly forced to recognize a visual style … simultaneous with a type of femininity. The two cannot be pulled apart. The image suggests there is a particular kind of femininity in the woman we see, whereas in fact the femininity is in the image itself, it is the image—“A surface which suggests nothing but itself, and yet insofar as it suggests there is something behind it, prevents us from considering it as surface” (JeanLouis Baudry 30).

Cherry Coke, bikinis, and Lolita glasses aren’t indicators of self-hood any more than the tone of Del Rey’s music itself is for me, which is to say also that the sonic sense of Del Rey, which is simultaneous with various genres of being, are also not “her”.

Just as Williamson notes the black dress can’t make the femme fatale, I don’t think the baby voice can make the ingénue, or even that a refrain of “he hit me and it felt like a kiss” can make a victim. Although the style of the little black dress appears to be in the femme fatale genre, we don’t know. We don’t have that access. We do have access with a line like “he hit me and it felt like a kiss” in which the genre is clear, yet the feeling is “a kiss.” It seems lyrically, Del Rey willfully subverts her surface presentation.

It is perhaps exactly through the misuse of the apparatus[3] that a “performed sincerity” is accomplished. Precisely because Del Rey acknowledges through her many irreconcilable personas that she is gesturing towards not a style of personhood or right relation to self, but to styles of performance which depend entirely on reciprocity with a receiver. It is because this receiver has been abstracted via their engagement with Del Rey’s misuse of the apparatus and its impact on the genre, that an arena of genuine encounter is achieved for both listener and sender. Perhaps you don’t listen to Lana Del Rey in the moment when, in a voice which sounds half as kitsch as Nancy Sinatra doing “Sugar Town,” half as sinister as Nancy Sinatra doing “Bang Bang,” Del Rey sings “Serial Killer”—perhaps you become the listen itself:

Wish I may, wish I might

Find my one true love tonight.

Do you think that he

Could be you?

If I pray really tight,

Get into a fake bar fight,

While I’m walking down

The avenue.

If I lay really quiet,

I know that what I do isn’t right,

I can’t stop what I

Love to do.

So I murder love in the night,

Watching them fall one by one they fight,

Do you think you’ll

Love me too, ooh, ooh?

Baby, I’m a sociopath,

Sweet serial killer.

On the warpath,

‘Cause I love you

Just a little too much.

Perhaps instead of arriving at a point where you consume the pop culture trinket Del Rey offers, the hydra-nature of Del Rey’s composition of addict, girl, lady-gangster, sociopath, noir film star, LA dream pop goddess, &ct. erupts and you are instead not consuming, but consumption. In this way Del Rey admits her form of sincerity is sort of like not being the words of your poem, but being poem. This is a wild, ungoverned place to be, because it is a circuitry which doesn’t break, but instead re-circuits and has no use for sheathe of the wire.

Sherman said something a lot like this of her reasons for creating her Centerfolds series, “In content I wanted a man opening up the magazine suddenly to look at it with an expectation of something lascivious and then feel like the violator that they would be.” It’s important to note here that the twelve Centerfolds all feature a supine Sherman displayed across a twenty-four by forty-eight inch spread composed in the manner of a tradition pornographic or fashion centerfold—tribute is paid the original delivery method from which this genre arrives and then is subverted, occulted, in order to present a separate genre. Occulted in the sense that these images cease to retain their original meaning at all. They are no longer pornography, however, they are also not only a subversive re-channeling intended to subvert the image’s original message. Rather an unbound performance is accomplished in which the image entirely occults its original meaning and the actors playing within the rhetorical situation which make the image/song/artifact relevant are themselves reformed as meaning makers. This is to say that the images are not even simply subversive in the sense that subversion depends upon the frame it is subverting; these images act so outside of the frame as to forget their source entirely.

This occult presents not a separate entity of the woman portrayed herself, but as we read Sherman suggests, a new genre of readership entirely. For Sherman, she unwinds the genre of this shot from “lascivious” erotica to “violated,” something closer to pornography. While many have wished to insist upon the manner in which the male gaze becomes vilified, what I read and align with Del Rey here is the way the vulnerable ability to allow a gaze which enables a circuit of reciprocity at all is exhibited—even if that circuit of reciprocity potentially links with the masked and irreconcilable persona presented by Del Rey. In effect, this mode of circuitry suggests a style of reciprocity which in turn suggests no center or core “value” other than the desire to send and therefore rends itself vulnerable; although these shots are yet another costume on a costume; are more rings that spell “BAD” in fake gold, they also insist on an inquiry into the desire genre which must ultimately expose itself through its very need for an audience.

Earlier, I suggested that Del Rey is never acted upon, but is always the actor in these songs. What I mean is 1.) she enacts a vast persona-project in which multiple characters are posited and 2.) she possesses an ultra-agency which is often so over-imposed that it attains a violent nature. I also mean to insist that the enactment of such a project is empowering in a manner we often do not acknowledge because it entails an erasure of the self. A more clearly empowered pop star, take Beyoncé as an example, displays through her consistency of persona, message and sound that she is a “Grown Woman” who would never suggest domestic violence or suicide are interwoven in the texture of the romantic discourse, would simply never suggest that the discourse is more nuanced than is palatable[4]. Beyoncé is fascinating as the extroversion—the accepted radical—for, she too, posits her own radical subversion via a total shut-down of the reciprocal romantic system through frequent displays of female utopia.

Del Rey’s extreme turn in the other direction, however, suggests another style of radicality which is also an empowerment: the vulnerability implied by a life lived fully in unrelenting relation to desire (what some critics have, at points, correctly, some points incorrectly, named “addiction”). Lauren Berlant’s writing from Sex, or the Unbearable on affect, mourning and desire, helps me think through this, especially this suggestion:

Since misrecognition is inevitable, since the fantasmatic projection onto objects of desire that crack you open and give you back to yourself in a way about which you might feel many ways will always happen in any circuit of reciprocity with the world, why fight it?

It’s a strange gesture to align Lana Del Rey and Lauren Berlant, but I am enamored with both for their implication that desire is the breaking technology which can reintroduce us to ourselves, as opposed to another. I don’t hear this sentiment on the pop radio much—nor do I really mean to suggest that the basic airwaves should be flooded with phrases like “With the rate I was going, I’d be lucky to die / I was born so bad, not naturally right” (“Every Man Gets His Wish”) or “Being a mistress on the side, / It might not appeal to fools like you. / … But you haven’t seen my man” (“Sad Girl”). But I do think that an acceptance of approaching others with the understanding that you will suffer “misrecognition” and that this isn’t negative, but rather an opening, can be generative.

That, in fact, the masks Del Rey affixes to re-circuit the apparatus allow a higher order of desire. Berlant writes the “incoheren[cy] in relation to desire” which “does not impede the subjects capacity to live on, but might actually at the same time, protect it” allows for an elision or transcendence of archetypal roles like “mistress” or “prom queen” beyond their simple desire capital into a personal mode of sincerity. In other words, in a Del Reyian model: one is always one’s own mistress, one’s own prom queen in a circuit of reciprocity in which the sincerity of one’s energy or capital are determined not by outside systems, but by one’s constant ability to recalibrate in the encounter with the other. To make a costume change, switch wigs.

There are two moments when I am struck by a concept of Del Rey as a person, when I feel as though the half tragic, half Copacabana nom de guerre—after all, it always seems like stardom is a style of war for her—sheds itself and I think of the manner in which Frank O’Hara comments on the other Lana (Turner’s) intense fragility in the last few lines of “Lana Turner Has Collapsed”:

there is no snow in Hollywood

there is no rain in California

I have been to lots of parties

and acted perfectly disgraceful

but I never actually collapsed

oh Lana Turner we love you get up

The way O’Hara notes her friability, but also seems to suggest that it is this very quality which renders her more transcendent than himself is what amazes me. It is as though it is the very capacity to transcend in the environment where there are “no snow … no rain” and where no matter how “disgraceful” one acts it is only Turner who can exit out of her stasis into “collapse.” It is Turner who achieves, through her ability to fall, to faint, a desired syncope. This—a rise in the fall—occurs on the necessarily unpunctuated line:

oh Lana Turner we love you get up

which lifts the starlet from corporeal unconscious to spiritual adoration, even declared love, both of which can only be achieved because Turner is a person whose composition is one of intense breakability—like other beautiful and hard to handle entities: sand dollars, sequined gowns, shale. When she ceases to circuit with over-shocked receivers in order to energize herself, so, occasionally, is Del Rey. These moments, when I’ve come upon them for the first time in her songs, have been something like a shock receiving a shock for me, or perhaps a mirror mirroring into another mirror. The first moment is from a lyric in “Brooklyn Baby”: “They say I’m too dumb to sing / They judge me like a picture book / By the colors, like they forgot to read” and the second is in an unreleased song titled “Every Man Gets His Wish” in which the singer actually refers to herself by the name “Lana Del Rey”:

I learned how to make love from the movies

He found me waitressing at Ruby Tuesdays

He said I wanna buy you a classic white milk shake

I said I’ll serve you up a special side of heartbreak

(Special side of heartbreak)

I was working down at the corner cafe

You drove me in a Chevrolet

Whistle at me as my hips go sway

Lana Del Rey how you get that way?

(How you get that way?)

The self-reflexive moments in which Del Rey sings that other suggests she is “too dumb to sing”—not to write words or music, but to actually use the human instrument granted to us all as “in direct contact with emotional impulse, shaped by the intellect but not inhibited by it” (Kristin Linklater)—and that she is “judged…by the colors” which have no value beyond the “surface which suggests nothing but itself” (Baudry) both impart a quick understanding on the part of Del Rey as to her own operation of the apparatus. Or rather, if the many songs addressed to the “other” in the work of Del Rey and all the sonic gaze into the camera are simply a masquerade maneuvered in order to engineer an affective zone of sincerity somewhere in the futurespace, then the ultimate cri de coeur of Lana Del Rey seems to be this one question addressed not to any other, but to herself, in the line “Lana Del Rey how you get that way?” This line becomes both recognition of this system of gestural sincerity and radical vulnerability and inquiry into its operation; it becomes a manifesto made of papier-mâché. If I am talking about piñatas, what I mean to say is: at the interior of Del Rey’s poetics, I wonder if there is a space of more interior, a positive vacancy.

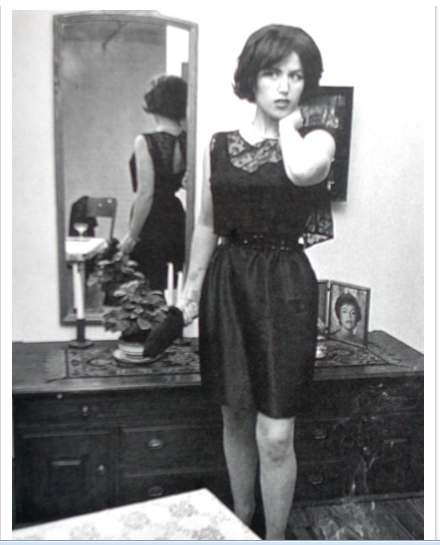

In this Untitled Film Stills #14, the viewer sees Sherman alone at what I have always thought of as a dinner party or date in her own home. She holds a sheathed cake knife and looks worried about something happening in the next room. I bring this photo up to point out that surrounding the frozen figure of Sherman are other Sermons—herself in the portrait on the credenza behind her as well as her own reflected back in the mirror, so like Del Rey, the gesture isn’t to locate the other, but to locate the self to the self while in the middle of the moment. In fact, this photo seems to me to be about keeping the self about the self in an effort at creative generativity. That much like the frequently charged or vacant gestures of Lana Del Rey, Sherman’s sheathed cake knife is a necessary appendage for an artist who presents in many masks as a mode of vulnerability; it can be difficult to retain the self-center when the center is so vulnerable as to be selfless.

Candice Wuehle is the author of the chapbook cursewords: a manual in 19 steps for aspiring transmographs (forthcoming from dancing girl press this spring).

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

[1] In addition to select verses off Ultraviolence, many of which are lyrically reworked and energetically rechanneled from the last few year’s unreleased songs.

[2] Del Rey situates herself in Americana clearly in songs like “American” or, to choose my favorite example, with the bizarre Hopper Del Rey performs a surreal ekphrasis of in her Whitman ode “The Body Electric”: “Elvis is my Daddy / Marilyn’s my Mother / Jesus is my bestest friend … We get down every Friday night”. The trinity Del Rey genuflects to under the auspice of the most erotic poem in the American cannon is distinctly pop cultural; it belongs on the dashboard of a Chevrolet, which is also the most modern American symbol: the mobile altar.

[3] I mean apparatus here as the delivery method through which the genre is delivered; the album, or album label, itself as the technology through which we are deposited Ultraviolence, for example. It is not what we listen to, but how it arrives through our senses.

[4] Take again an example from “Body Electric”: “Heaven is my baby / suicides her father / opulence is the end.” The product of sexual merger are, for Del Rey, heavenly bodies. This is on par with Beyoncé, however, the only route to an ethereal or spiritual plain is via what Del Rey suggests to be the ultimate “opulence” or autonomy of “father” “suicide”. I think we can easily read this to suggest no positive outside encounter with a romantic entity is available, and thus the availability of suicide becomes a mode of self-sustaining spirituality which in turn actually aids the failures of the love contract.

Bibliography

- Berlant, Lauren and Lee Edelman. Sex, or the Unbearable. Duke University Press: 2013.

- Linklater, Kristin. Freeing the Natural Voice. Drama Publications: 2006.

- Sherman, Cindy. The Complete Untitled Film Stills. The Museum of Modern Art: 2003.

- Williamson, Judith. “Images of ‘Woman’: Judith Williamson Introduces the Photography of Cindy Sherman”. Screen. 24.6 (1983): 102-116.

Leave a comment