Foy’s Made to Break follows a group of friends on vacation. They are staying at a cabin in the woods. And like any good cabin in the woods, it becomes more perilous with every page. Readers are treated to storms, mudslides, car wrecks, grave illness, and injury. On top of that, factor in a cryptic old man named Super who may or may not be a little deranged. One character even bluntly references Occam’s razor while reflecting on the entire shit-storm. It has all the makings of a campy horror flick, but Made to Break is more than the sum of its plot twists. The novel is about digression than progression. This isn’t to say there’s no forward plot momentum—it’s got drama, some messy romance, and life-or-death stakes—but Foy’s work finds its most convincing voice when it wanders into tangential territory.

Foy’s book is filled with side notes. Some of these are told through characters swapping drunken stories, others come in the narrator’s fractured soliloquys—something like stream-of-consciousness on amphetamines. These miniature stories provide glimpses into these characters. The stories are told like “remember the time when …” anecdotes. Most of these memories are only funny or profound in hindsight—in the moment, chances are the characters weren’t laughing. After an entire novel of these digressions, the reader becomes increasingly aware that this group is emotionally wounded and running on fumes.

And of course there’s that B-flick theme at work too. You’d be hard-pressed to call Made to Break a horror novel, but Foy plays with enough overlapping horror tropes to render the genre an effective framing mechanism for discussing the novel. As the book continues, the ominous cabin becomes more ominous, more deadly, and a generally crappy place to be. However, the group of friends cannot stop telling their little stories. These stories sustain them. It’s impossible to ignore the similarities to campfire ghost stories.

I’m reminded of a documentary called Nightmares in Red, White and Blue: The Evolution of the American Horror Film. In the film, John Carpenter says “there are two kinds of horror movies … we’d imagine ourselves around a campfire, and the wise man or whoever is talking to us about the location of evil. And he says the evil is out there in the dark. It’s beyond the woods. It’s the other tribe. It’s the people who don’t look like us, that don’t speak like us. And that’s the external evil.” In Foy’s novel, this is represented in the main plot; the cabin, the storm, the creepy old guy—the external factors, the “other.” These are easy thrills. Any idiot with a camera can make that kind of horror flick. But Carpenter goes on to say that there is a second type of story. He says “Same setting: the campfire, the shaman, the wise man says ‘Actually the evil is right in here. It’s in our own human hearts.’ That particular story is the harder one to tell … it’s harder to say ‘I have met the enemy, and he is us. We are the enemy.’” In Foy’s novel, this story is found in the subplot. It’s found in all the tangents, steeped in sex, drugs, and obscure references to film, literature, celebrities, and historical figures. It’s in the torrent of memories these characters share around the metaphoric campfire. All while the external world collapses and demands attention.

While the sideline stories sometimes appear trivial and pointless, those stories are more important than the plot itself. Foy’s main plot is filled with fluke accidents and fucked up karma—and that’s a big deal; it keeps the novel moving—but these external forces are simple to explain. This type of drama and suspense occurs any time lightning strikes. No brainer. What’s harder to explore is the inner turmoil—the parts of each character itching to break wide open.

Foy’s novel thrives through a sort of anti-plot. Made to Break explores what really matters even when the shit hits the fan. The digressions make this story work. While they can sometimes drag on, the main plot would suffer without them. Made to Break is a maximalist story with a relatively minimalist plot. And it works. It’s an intriguing read if you can get through some slow build-up and constant tangents. As I said, these distractions feel necessary. Still, you could argue that Foy might’ve achieved the same effect in fewer pages—this story could be pared down to novella-length and still pack a punch—but Foy makes sure the sentences are constructed artfully enough that you’re willing to keep reading either way. His maximalist prose gives you something to enjoy even when the plot isn’t grabbing you.

Foy’s debut work is ambitious, and its complex character arcs intersect in surprising ways. While some parts of the main plot feel like clichés, his book is more about small moments between characters, so it’s easy to forgive and get lost in each subplot.

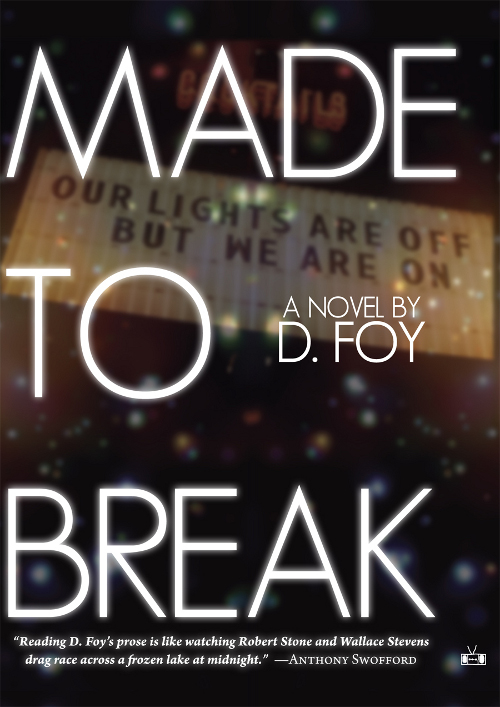

Made to Break, by D. Foy. Columbus, Ohio: Two Dollar Radio. 218 pages. $16.50, paper.

James R. Gapinski’s fiction has recently appeared in Line Zero, theNewerYork, and the Pink Fish Press anthology, Involution. He holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Goddard College, and he currently teaches at Pueblo Community College. James lives in Colorado with his partner and the standard hermit’s assortment of books, video games, and cats.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

Leave a comment