There is a cold wisdom shining through the stories in Jac Jemc’s A Different Bed Every Time, a detached and wry intelligence that seems to let us watch from over its shoulder, smiling commiseratorially, but never quite telling us what it sees. The stories we witness here are often surprising, sometimes surreal, and frequently heartbreaking, but they are all united by the singular confidence of Jemc’s style—assured, controlled, and clean. We feel a strong hand on the rudder of this book, even when we cannot quite make sense of the individual pieces as we pass through them. There is a cumulative quality here, a vision of a world being freshly and bravely explored. The sentences are crystalline and glorious—distilled, lithe creatures—and their sheer artfulness is one of the primary pleasures of the book. While the stories are not explicitly linked by content or form, Jemc’s voice is a powerful and central force throughout the collection. The craft of the writing—its beauty and its incisive spareness—is what keeps us moving forward far more than the plots of the individual pieces, which tend towards the fabulist and the oblique. The structure of the stories seems, often, to be simply a frame on which to hang the language, and that is no flaw. The language is where the real emotional punch lies, and the language is as near as anyone should ask to perfect.

Like Jemc’s debut novel, My Only Wife, the stories in A Different Bed Every Time circle around absences, and Jemc shows a profound skill in continually pointing us back towards what is not there, what cannot be said or seen. There is frustration in this—like a description of a color you’ve never seen or someone else’s memory of you which you do not, yourself, remember—but it is a carefully-wielded and expertly-crafted frustration. Certainly some of these stories feel inaccessible, beautifully-made but obscure, and most deny us the easy rewards of simple character identification and narrative fulfillment. These are not stories that unfold themselves to the reader, that envelop in human understanding. Instead, they seem to position themselves outside of any straight-forward viewpoint at all, as if they emanated from some impartial and bemused observer. There is something final and profound in the stance, something godlike, something that observes all this human frailty and mishap with a shrug.

For all its distance and austerity, however the prose is never clinical—indeed, there is something comforting in the starkness of the writing, in the way that even profound tragedy is inspected with an unwavering gaze, as if to say “this too is just how things are.” In the story “Hammer, Damper” a young child is dying of a long but unnamed illness. The child is not named either, nor are his parents. All the characters seem to be falling into step with some external machinations, some power beyond them: ”The flame of the child is dying out. Words spread quickly as they make their way down to the valley of the cafeteria. The parents torch themselves with coffee, uttering on the view from every window. The mother hisses and spits, and with time they begin to compose themselves with the tenderness necessary to return to the child.” Or, in “The Wrong Sister,” a woman stands in for her twin and quickly realizes that her sister’s husband plans to kill the woman he believes is his wife. She decides that the best plan is to let him commit his sloppily-executed crime and get caught for it: “The birds keep chirping, but you’re still convinced you cannot get gone enough. He’s sure this will solve all his problems, but you know this gesture will be read like a wasteland. It doesn’t matter what’s been or what will be. Tenses have been paved over.” Many of Jemc’s stories take place in this tense-less (and, in a certain sense, tensionless) space when decisions become unimportant and personality moot—everything is running on rails towards an inevitable completion.

What we get instead of plot twists or vividly-painted psyches is an astute attention to detail and an ability to make the world itself—the background thrum of people, places, and things—feel intensely new. The arm’s length position we are often placed in by these stories becomes a distinct advantage here; we are given the space to see the strangeness of the ordinary, and the possibility of the strange. Absurdism and realism drift together seamlessly, the characters act reasonably or unreasonably, and we stand back and watch, and no matter how outlandish or painful the places this momentum has carried us become, we accept and examine it all. This is not to say that the stories are really poems at heart, eschewing the usual marks of narrative construction: plot or character or catharsis. There are characters and actions and linear stories running all through the collection, and while there is certainly an element of the nouveau roman, I do not think that Jemc’s project is to dismantle the formal elements of short story writing. Instead, she gives us stories that are a both odder and cooler than we expect, immersed as we are in a confessional age. For these characters, it seems that confessing would be a great relief, almost an indulgence—if only they could find the words. Therein lies the real, tender heart of this collection, and the real achievement of the exceptional prose; Jemc has taken her brilliant, insightful words, and steered them directly into the wordless and the inexpressible, as if to use that little light to map the shape of the greater darkness beyond.

There are no easy conclusions to be drawn from A Different Bed Every Time; this is an ambitious book that builds its foundations on the slipperiest of materials: small images and collections of words, not all of them said aloud. Not every story succeeds; there are moments when the loveliness of the writing is not enough, and I found myself wanting something warmer, just some bit of the familiar to grab onto. But the collection as a whole succeeds remarkably. There is a great deal of poetry and a great deal of truth in these stories. They require work, and they expect you to chase them, but the rewards are enough, and you will.

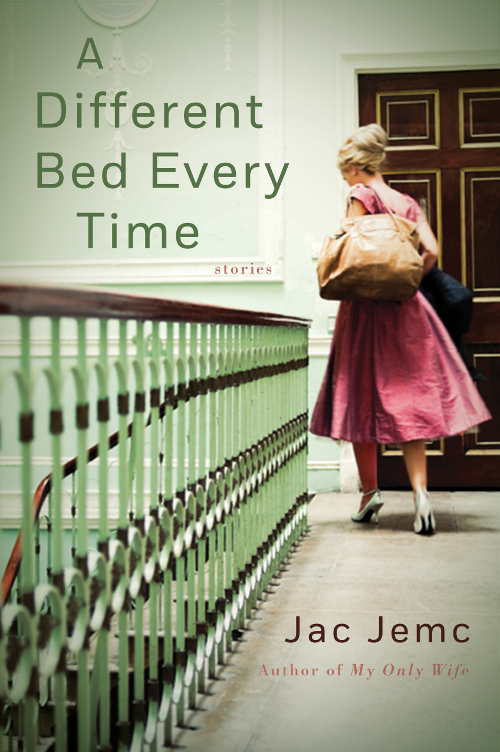

A Different Bed Every Time, by Jac Jemc. Westland, Michigan: Dzanc Books, forthcoming. 184 pages. $14.95, paper.

A native of a decaying Pennsylvania steel town (the one from the Billy Joel song), Emily Kiernan writes about islands, vaudeville, implacable but unjustified feelings of abandonment, the West, and places that aren’t the way she remembered them. She is the author of Great Divide (Unsolicited Press, 2014) and a graduate of the MFA writing program at the California Institute of the Arts.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

Leave a comment