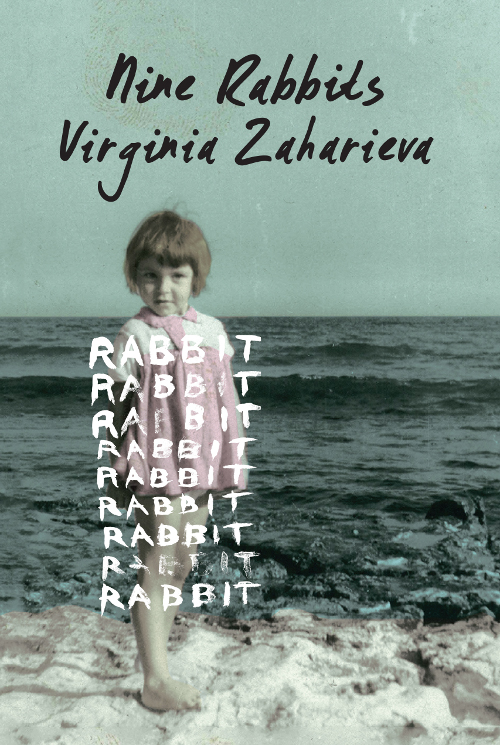

Manda, Virginia Zaharieva’s fictional alter-ego in her intensely autobiographical first novel, Nine Rabbits, leads the kind of wild, globe-trotting life that would make most people envious. A successful poet, magazine publisher, television and radio personality, mother, and psychoanalyst, she’s dogged throughout her life by the abuse she suffered as a young girl at the hands of her bitter grandmother.

Originally published in 2008 but only recently translated from the Bulgarian into English with support of the Elizabeth Kostova Foundation for Creative Writing by Angela Rodel, Nine Rabbits is a novel without illusions. Characters are portrayed in a stark light exposing their neediness, their unflattering traits, and, as the novel progresses, their hard-fought wisdom.

The novel begins in the mid-1960s with Manda, “an inconvenient four-year-old grandchild,” at her grandmother Nikula’s house in seaside town of Nesebar, on the Black Sea. Her parents have recently separated and her mother, forced into “pulling double shifts in order to pay the lawyers to fight for me,” could not care for her.

Her grandfather Boris, an itinerant laborer and gardener, is away working for months at a time:

He would come back now and again, make another child, and then go back to his tomatoes. My grandmother brought up her children alone with the money he sent her. She worked in strangers’ fields and stored up intense rage toward him, since he wasn’t around to witness her heroics.

Her grandmother harbors anger at being alone and begrudges him for his infectious cheerfulness:

My grandmother hated him most of all for that—for the fact that he never stopped having fun. […] For her, dancing and craziness didn’t have any use, so she treated them with scorn—or rather, with the envy of the punished.

Young Manda, unfortunately, shares her grandfather’s zest for life. Her grandmother beats her and stabs her with sewing needles. After Nikula ties her down and whips her with nettles, injuring her so severely that she awakes “tightly wound in bandages,” Manda’s mother finally whisks her away for good.

And so it seems that Manda is rescued. She grows up, marries “an heir to a rich family,” bears a son, gets a good job, publishes well-regarded poetry collections, goes to school and earns a degree in psychotherapy, travels widely and buys expensive clothes, yet despite all these signs of success and the good life, one senses the emotional scars of her upbringing. She’s stunningly uncomfortable at being herself and intermittently loses all confidence in her abilities.

Her husband starts sleeping with her younger sister: “He hates every sign of joy and freedom in me and desires me passionately only when I am in the depths of despair.”

~~~

The most unexpected thing about Nine Rabbits is the twenty-five recipes for traditional Bulgarian culinary dishes that are spread about throughout the text. In the middle of a chapter about Manda and her grandfather gathering tomatoes, there’d be a note that a “monastery was famous for its tomato soup,” and then, set off by a different font and a little bunny insignia, will be the recipe for that famous soup. Although sly bits of whimsy (“When it is ready, cut a slice of the aroma and put it away for days when you urgently need to create coziness”) and oblique cues as to Manda’s state of mind are occasionally embedded within the recipes, most appear without creative embellishment. Nothing about the recipes make them essential to the narrative, so their inclusion is initially puzzling.

And yet there’s something about food that probes at the central dilemma Manda faces—whether to “put up” with an unsatisfying relationships and gender roles or seek a fuller, more pleasing life for herself. The tomatoes, potatoes, peppers, and chicken livers that make up the ingredients might provide little more than mere sustenance; in the hands of a caring and creative chef, however, great delicacies could also arise from such mundane ingredients.

The food metaphor also allows us a chance to consider how bitterness is a conscious choice. Nikula, who’s otherwise described as a fantastic cook, acts out her spite by cooking truly horrendous meals for her husband.

The day after a pair of beloved pet cats (Topsy and Mopsy) abscond with a batch of freshly-stuffed sausages, Nikula serves a delicious dish of rabbit and apricot dumplings:

This fragrant dinner lightened up the gloomy atmosphere of the preceding days. They ate and drank, and at one point Boris asked, “Well now, woman, where are Topsy and Mopsy?”

“How should I know? They ran away, like the devil’s spawn they are. How could they dare come back now,” my grandma replied angrily.

Boris pushed the food around on his plate and sat down his fork. The children followed him closely with their eyes. All at once, the whole gang realized what had happened and rushed outside en masse to throw up in the yard.

~~~

In grad school, while pursing my MFA, I stepped into a discussion about the apparently exalted state of post-war Polish poetry. Mind you, as a fiction writer with no real knowledge on the subject matter at hand, my end of the discussion was limited to a few thoughtful nods, but my friend was adamant that totalitarian communism was the best thing that ever happened to Czesław Miłosz. Never mind that his countrymen were ruthlessly persecuted. Like the crushing pressures and intense heat that give birth to diamonds below the surface of the earth, communism wrung Poetry from Miłosz!

Needless to say, my friend had a dim view of contemporary American poetry, which he thought had been rendered flabby by the bourgeois comforts and freedoms of our material abundance and open democracy.

My friend would not be Nine Rabbits’s biggest fan. Although the heady stuff of political oppression occasionally raises its head (Manda—and Zaharieva— after all grow up in communist Bulgaria), the adult Manda lives in an enviable material comfort.

I could imagine my friend flinging down this novel. The novel’s most cathartic scene takes place during the kind of dilettante-ish calligraphy retreat that the housewives of Beverly Hills might attend.

“Calligraphy is a soft paw on our souls,” Manda muses.

I can almost hear my friend chortling at this.

And yet Manda’s struggle to cement her self-hood is authentic, one many can identify with. It’s rare for me to recommend a novel on the strength of its wisdom, but time and again I found myself nodding appreciably as Manda moves towards a uniquely feminine Zen understanding of herself.

Lazing in the Parisian square in front of the post-modernist Centre Georges Pompidou, Manda watches

the pigeons battling for seeds at the clock’s foot and notice[s] a bald pigeon with a patch of dried blood on his head, trying to climb up the sloping brass pedestal. His little red legs energetically gather speed as he manages to reach about halfway up, but after that he slides back down, where several of his vicious brethren peck at his injured head.

Existence teaches me its lessons:

“If you have wings and don’t use them, they’ll kick you down at the bottom.”

Nine Rabbits, by Virginia Zaharieva (trans. Angela Rodel). New York, New York: Black Balloon Publishing. 186 pages. $14.00, paper.

Nick Kocz’s short stories have appeared or are forthcoming in Black Warrior Review, Five Chapters, Mid-American Review, The Pinch, and, most importantly,Heavy Feather Review. A graduate of Virginia Tech’s MFA program, he lives in Blacksburg, Virginia, with his wife and children.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

Leave a comment