It’s no secret that fire sign Dorothea Lasky believes in ghosts. Besides the essay “Poetry, Ghosts, and the Shared Imagination,” in which she quite literally says so, one might notice the phantoms that haunt her poems’ yellow hallways. They might need rain boots to avoid the floods of milk and blood coming from God knows where. Specters are liable to rise out of the bathtub in Room 237 with hopes that someone who looks like a fuckable Jack Nicholson will show them the time of their life—or maybe just a little acknowledgment.

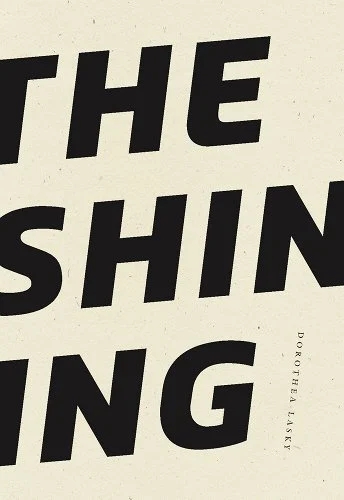

Her newest collection, The Shining (Wave Books, 2023), is a book length ekphrasis of its namesake. She’s probed this subject matter before. The previously mentioned essay in Animal (Wave Books, 2019) uses the film to discuss Lasky’s own understanding of poetry as communion between writer and reader. You don’t have to go past the opening poem of her previous collection, Milk (Wave Books, 2018), to encounter another blood-filled hotel.

But even if you can see Lasky circling around the subject matter in her past titles, and even if you’re familiar with her distinct style—the Merwinesque lack of punctuation, the subtle diction, the who is and isn’t the speaker—the high concept still yields plenty of goosebumps. Take “Old Photo,” for instance, an earlier poem in the collection whose opening stanza gives an idea of the contradictions that lay ahead:

It says 1921 in the picture

And I am smiling

But it’s not me anymore

Or maybe it never was

Lasky’s mischievous metaphysics are on display here. Her slippery usage of self at times recasts The Shining of King and Kubrick into a tale of complex and bruised monstrosity. Female personae evade and ignore trauma, as in “Twins” and “Blue Christmas.” They end the collection bereaved and confused, still ready to fight the spirits off, wandering the mountains and breakfast buffets looking for sensual relief. It’s not gory revenge. It’s a painful repossession.

Both the Kubrick and King stories also point at Jack Torrance’s failure to create art as a source of his rage. Lasky’s poems take this issue one step further. They make you consider the film and novel not just as a descent into violence but as a story about artists, their passions, and their effect on those they love. In “Poetry Hates You Too,” the closest any poem in The Shining gets to an official ars poetica (including its own Marianne Moore allusion), a ghostly male poet becomes not just a charming loser but the portrait of an impotent misanthrope:

No instead I dedicate this poem

Dead and useless as it is

To the man who sits at his wooden desk

Constructing the annals

Of that conservative leaflet

No one would die for

Strumming his computer keys

Like the way he fumbles with a clitoris

There’s no direct reference to the Jack Torrance character in this poem, but how many people will hear the phrase “the man who sits at the wooden desk” in the context of The Shining and not think of the terrifying document (which, in some circles, could almost be considered sly conceptual poetry) that reveals Jack’s madness?

That is the nature of the ghosts in language that Lasky knows so well, how the in-between of language can take on the quality of haunt and suggestion. Now, you experience the phantoms firsthand. Questions occur: are we inside the Overlook Hotel? Whose eyes do we look through? The poems zoom out, then zoom in, then cut to the B storyline, then back to A. Iconic moments now play differently, such as in “Red Rum”:

I have taken my red lipstick

And written Help across my chest

He looks at it so kindly

I know I am real again

More ghosts creep into the Moon Room all the time. Images, objects, colors reappear not only from the film but from one poem to the next, sometimes repeated, sometimes rearranged. The carton of eggs, the blue/blue/purple dress, the “Red Rum,” the “Red Airplane.”

In “Blue Hallway,” one of the more freewheeling poems in the collection, you’ll be following Wendy, AKA the Speaker, AKA no one through the hallways as they flee for their life:

I feel everything so acutely

Despite the lack of acute attention

My husband is trying to kill me

I am trying to outsmart him

But all around me are the ghosts

I turn my head and see a bear and a man

This isn’t at all the way I imagined it

I have learned not to imagine anything

I keep running with a knife

And then later in the poem, there comes a disturbing peace. The chase has ended in a moment so indicative of the jump-cuts that give The Shining a sense of trickery and surprise:

I am in the space

That has kept me up every night

Even my brother is finally here

We are having a party

I get out the cut cheese and meat logs

People discuss their hair

Maybe Wendy’s the poet and the killer. Maybe they’re all just ghosts after all. Maybe I’m a poet, and you’re a ghost-bee. Maybe you’re the reader and the killer and all these ghosts are just cleaning your clothes and handing you the ax. No matter the truth, just remember: it’s all poems in a book, Danny. It isn’t real.

The Shining, by Dorothea Lasky. Seattle, Washington: Wave Books, October 2023. 96 pages. $18.00, paper.

Stephen Meisel is a writer living in Atlanta, Georgia. His fiction and poetry are published/forthcoming in X-R-A-Y, Maudlin House, and Chariton Review. He can be criticized or complimented at meiselstephen@gmail.com.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

Leave a comment