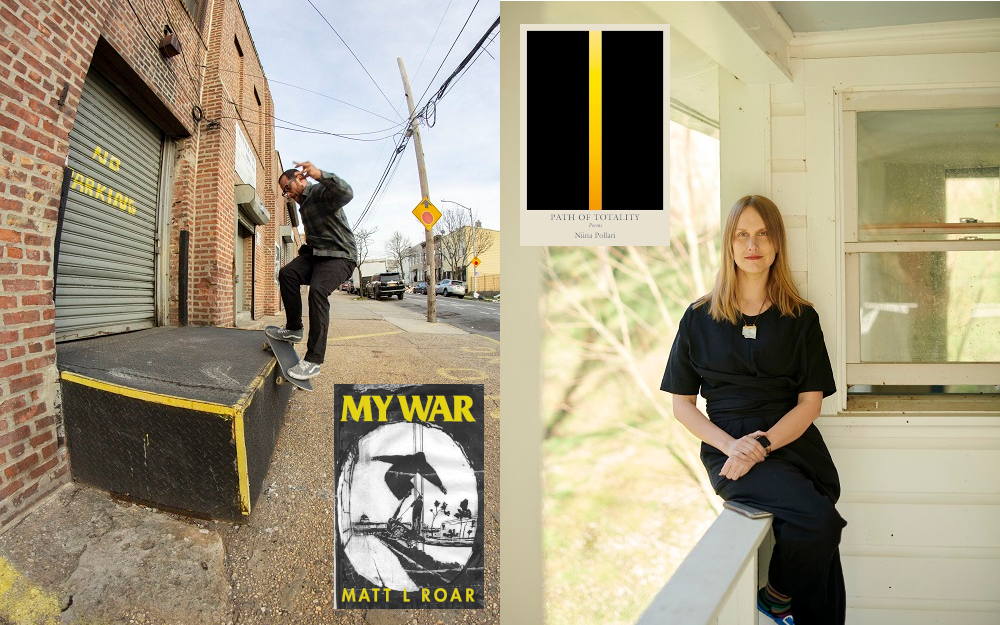

I first read Niina Pollari’s Path of Totality on a plane and was immediately torn between giving into the book, allowing myself to weep my way from JFK to SFO, or to pull myself together and not thoroughly weird-out the passenger in the neighboring seat. Niina’s book is funny and smart and sad and intimate enough to where I didn’t have a choice. The momentum of this book pushed me through in one sitting. As anyone who has processed trauma or worked through grief knows, letting go of control and allowing the pain that’s stuck in our body to move around, express itself, be tended to, is at once painful, scary, and relieving/reprieving. Sometimes, when we witness someone courageously sharing their pain, like Niina’s poems surrounding the death of her daughter do, the pain stuck in our body can loosen up and shift around. Like a seemingly dead vine that has sucked up water and melted back to life, our pain begins to move and offer up new leaves, fruits, or flowers, shedding dry brittle branches. Niina’s book helped me do that. And I think that’s the best we can hope for after a terrible loss, to keep things in motion. Path of Totality was written after the loss of the author’s child. My book, MY WAR, was written after losing a dear friend to suicide. They say grief hits in waves. In surfing, there’s a phrase for when the ocean goes flat for a while, then a larger group of waves materializes out of deep water, catching everyone in the water off guard. It’s called a sleeper set. It’s scary because you can’t control them, can’t plan for them, and you’re often out of position, overtaken by them, rather than riding them. Those waves are also what you’re waiting for, what some deep, sad, young, hungry part of you yearns for. Path of Totality is a gift. It took me for a painful beautiful ride that I didn’t know I needed, and the waves keep coming.

Matt L. Roar: I felt like your poems make these huge swings from minutiae/dailiness, i.e. killing a spider or talking to a cab driver, to the uncontainable enormity of grief (a huge fucking flame/that would destroy everything you love). I’m also struck by how funny your book is, while also containing an ocean of sadness. Can you share how/why that came about?

Niina Pollari: The swings became more noticeable to me after my daughter died. In grief you are in a trough, and you get through the day by focusing on the minute, the task, but then sometimes the proverbial wave—that eternal grief metaphor—crashes over you and you are just obliterated. I think the ocean is a good parallel for it because it’s like that; the enormity of it would frighten you if you thought about it too closely. Or maybe not you, since you’re a surfer. But I’m definitely more aware than ever of the hugeness of systems and everything that is outside of my control.

As for the humor. I don’t consider myself a “funny person” per se, but I think the absurdity that sometimes comes into focus from close examination is a big part of who I am. With my first book, I often heard from people about the humor: “I didn’t know it could be funny.” And the person who wrote the first book is present in this book too. I didn’t think about anything external for a while because I wasn’t able to lift myself out of the feeling. But then the outside world began seeping in again, and I felt guilty about it in a way, like I wasn’t supposed to feel things were funny anymore. That’s a strange sensation. I remember the first time I felt a desire to laugh after what happened, and it was after seeing a sandwich board outside this one coffee shop, and the sign said “Coffee: Because drugs are illegal.” It was so stupid to think that the sign implied I was only there to get coffee because I couldn’t get my hands on some nice drugs, but at the time it was also kind of true. And this made me sort of chortle darkly. And that dark chortle, unfortunately, is fundamental to my writing.

You have some humor in your book, too, but what struck me at first read was the tenderness. MY WAR is a book about young men, and it’s a book about skateboarding (the descriptions of which I found mesmerizing even though I know nothing about it), but there is also unbearable love in it that the you-narrator is sometimes anguished by an inability to express. Can you talk to me about the moments where he chooses to say or not say what his friends mean to him? What was the baffling communication like between boys who grew up, as you say in a poem, “before Desert Storm but after Vietnam”?

MLR: I love your dark chortle! It’s not unfortunate! I think that being a young straight cis man born in the 80s, it was pretty socially unacceptable to be emotionally vulnerable and open with your male friends outside of certain narrow constraints. Maybe dudes who played football could smack each other on the butt in the locker room, but I didn’t have access to that. I also grew up hearing Vietnam war stories from my dad and my friends’ dads, and from watching Forrest Gump, and kind of imagined this male intimacy (trauma bond?) to be inherent in the experience of these young men who were forced to go to war together.

Obviously the problem of men being cut off from their feelings still exists in our society, but we’ve kind of entered an era where, at least in certain corners of America, kids talk openly their sexuality, mental health, etc. I was shocked at how students of mine, when I was teaching high school in recent years, would openly divulge that they were in therapy with their classmates. When I was a kid, I remember my friends saying, “Why would you go to therapy when you could just talk to us?” And in my head, it was like, you guys call me “gay” if I say that I like how the water of the bay looks, or make fun of me if I hold my skateboard by the trucks for an instant. (“mall grab”) There are and always have been so many rigid rules young men have to follow to gain the acceptance of their peers, even in “cool” “anti-establishment” subcultures like skateboarding, graffiti, and punk-rock. Saying how much people mean to you felt like a huge risk. It still does. Like writing a poem. It’s opening up a nerve that someone can easily poke. That said, skating with your friends, filming each other, making music in a garage, or missioning to spray paint your name in a drainage ditch, were incredibly intimate experiences. They were these sort of underground socially sanctioned spaces where you could express your self, your -ism, and have someone actually SEE you, and hopefully say, “that was cool.” Skateboarding is like a form of interpretive dance that miraculously wasn’t shunned by alty cis-men. This is probably because the risk of injury and the constant conflict with normies makes it “tough.” Graffiti is similar, except replace risk of injury with risk of losing your freedom. A friend saying I had good style or appreciating my little piece of underground art was a form of validation I was so hungry for. I read with the poet Courtney Bush recently and she has this line that goes “Paying attention is the basic mode of love/ That doesn’t mean it’s easy.” Skating/punk/graffiti were the spaces we got and gave attention/love.

I’m thinking about your poem “Embarrassment,” and the Miranda Popkey quote you chose: “to indicate interest is already to expose oneself to humiliation.” In some ways your poem touches on how sharing your desire to have a baby, to love someone, is so vulnerable and induces shame, and how that feeling is so universal. Your poem raises the question, “So why did I feel so alone?” I know there’s not an actual answer, but for some reason, I still want to ask you to try to answer the question.

NP: To publicly say that you want to give and receive love is embarrassing. To do this and then ultimately lose is mortifying. I think I felt alone primarily because someone who used to inhabit my physical person was gone. This happens to anyone whose baby is born, and it’s startling even if the baby is safe and fine—that suddenly this presence who has been a part of your body is no longer inside. But the human experience is also already lonely, and conveying the colors and textures of the trash bouquet of our experience to another person is nearly impossible to do on an ordinary day. Add to that the stultifying, numbing, language-thieving nature of grief, and you are truly in communication hell. I said alone instead of lonely because I felt truly solitary. That’s some of it, but not all—I wrote this whole book, but I still don’t feel like I said everything. In some ways I will continue to feel alone about it until I die.

Your book is about the past, and about a lost era of your narrator’s, who is a version of you—and what’s lost is the transitory nature of young manhood, which you have to exit at some point or you die (actually or metaphorically). So you’re looking at the past, but it somehow both is and isn’t nostalgic:

The picture looks basically good but can you crop out the sadness?

Windchimes and sunshine ringing through the trees. Someday I’ll be dead.

Eating grapes. The grapes are gone. Then nothing.

I feel like you achieve this effect with a set of very specific imagery; in fact, often you seem to focus in on something like a picture would, freezing it and then examining it, the image of it. That way the water looks by the bay, which you mentioned earlier in our chat. Can you talk about your approach to imagery in this book? And your antidote for the trap of nostalgia?

MLR: I think I’m zooming in on some of those mundane objects as an attempt to bring in the present. Kind of like a grounding exercise after getting lost in the woods of subjective memory and emotion. Does that make sense?

Re: the nostalgia trap, I think I never got the memo that indulging in nostalgia isn’t cool. A few people have said things to me like “Wow, how do you avoid the pitfalls of nostalgia in your writing?” I’m not certain what they mean. I guess they are wary of a sort of revisionist history, where everything in the past is beautiful and great. So my antidote to that would be to try to be not necessarily truthful, but honest, by including the the painful/uncomfortable/complicated stuff of the past.

I think we have a tendency in our culture to idealize adolescence and young adulthood. Those times are very free and exciting, but the other side of that coin is not having the tools you need to set boundaries, having very little control over your world, and being sort of at the mercy of the people with power in your life. The process of individuating from your family and finding your people is so liberating and freeing, but it’s a difficult (and unending) process, and as an adolescent, depending on where you grow up, you’re kind of stuck with the people around you.

I love your line: “The fist of my heart almost unclenched itself, but I caught it.” I feel like it perfectly captures this mind/body experience of processing grief/trauma, and these sort of opposing forces within us. Where one part wants to let go of/ release/drop its guard, and another part wants to hold tight/protect/keep things secure. What are your thoughts on navigating that push/pull in your writing and as a human?

NP: Yes, I think you hit the nail on the head with your assumption about why nostalgia seems dangerous for people—what I see as treacherous about it is precisely that American tendency to think that things were always better before, which your poems decidedly do not do. I love the focused moments, and I love your use of the still image like a photograph to let the reader linger on an emotion, or an experience like growing up around a constant threat of physical violence. There is a lot of very sad violence in the world of your poems, but it’s neither downplayed nor the centerpiece of the poems. So this is very much in praise of MY WAR.

I have found the intimacy of “processing” grief really challenging, and still do. You will hate to hear this as a therapist, but I have never gone to any kind of therapy. I just bristle against processing; this is a part of the opposing forces you speak about. I guess my way of navigating it is writing what I hope are very truthful poems. Maybe that’s what (I hope) our books have in common: I want, even in employing a poetic device, to tell the truth. I think the truth is very much a thing you know when you see, instinctively, even as a reader.

Here’s an incomplete list of small details I noted in both of our books (I wrote them out in a list for myself when I was reading your book, as a way to remember): the phrase “down for whatever.” The phrase “life force.” Sardines. A tall can of iced tea. An injury past the skin, and down to the fat. And speaking of details, some people say that you shouldn’t write markers of time, or pop culture, into poems in order, to keep things universal. I don’t really agree with this; all my favorite poets get very very specific. Who are some of your influences on the poems in this book? Doesn’t have to be poets.

MLR: I’m not mad at you not going to therapy! It’s a good tool, but obviously not the only one. Re: universality, I’m with you. It’s pretty silly to think that you can write something that will be 100% universal across eternity and it’s also silly to think that the act of referring to specific references is not universal. The poets Becca Klaver and Marisa Crawford created this idea called Zack Morris Cell Phone Aesthetic, and Becca wrote this great essay for Weird Sister about it where she beautifully defends and articulates the conscious decision as a poet to include artifacts/details that we all know will one day be obsolete. I really love Joe Brainard, and think that his “I Remember” form is a huge influence. I love how he includes the mundane along with his intimate moments with friends and more thoughtful reflection. I went to school in the Bay Area and studied with Bob Glück and Dodie Bellamy. Their influence, and Kevin Killian’s, and that of all the other New Narrative writers, had a big impact on me. I love how they aren’t scared to write, unobscured, about sex and the body, and I love the way they allow form to be more complicated and messy AKA reflective of real life. I also found their blending of memoir/fiction, the choice to use people’s actual names, makes everything so much more exciting and charged. I’m working on a young adult novel right now with completely fictional names and sometimes I’m like “this is a joke,” who cares about this kid named Billy I just cobbled together. Lol.

“Down For Whatever” is a graffiti crew that includes a lot of surfers. I think there are individuals within skate, and graffiti culture who are huge influences on this book. I chose to reference these people and their tricks the same way somebody would reference Rimbaud or Greek mythology or whatever. While our culture has shifted and now we have skateboarding in the Olympics and there are graffiti tour guides operating in Bushwick, I don’t think there’s a true appreciation of the artistry, culture, history, sacrifice, and deep love for these art practices. Graffiti, punk music, and skateboarding share this quality of an underground community making it happen, sustaining the scene and the culture with (until recently) little to no opportunity for financial reward or stability. So I think my influences for this book are a lot of my friends. I read your book Dead Horse many years ago, and that’s just as much an influence on me as anything else, and Marisa Crawford’s writing, and my friends I skate with, play music with, etc.

I want to point the same question back at you! Who/what influenced this book?

NP: It’s hard to come upon direct influences but I sought out reading things I really wanted to read about grief, and I didn’t find many. I’ve mentioned in past conversations a few books about child loss, like Elizabeth McCracken’s memoir An Exact Replica of a Figment of My Imagination. And of course there are the books I consider a part of my poetic lineage in general, and my poet friends and editors, all of which and whom taught me to wield metaphor. But something I haven’t really talked about is the hundreds of blogs and Reddit posts I read about the topic of child death. I dwelled in this undersea of pain for months while I was trying to find the thing that made me feel seen. And while these stories might not be writerly influences, their emotional frankness about pain specifically, and about not letting it go, influenced me for sure. When I say I wanted to write something true, that’s what I mean. I wanted to write something that those people could examine and say “Yes, I know this feeling.”

We talked a little about this over text already but I want to ask about the place of nonfiction in your work. MY WAR has been called memoir, which to some degree shifts its focus from poetry for the benefit of the reader—what are your thoughts on the role of memoir, nonfiction, and memory itself in your work? Did you ever write MY WAR with memoir in mind or was this placed on your work afterward? Maybe that’s a good topic to end on.

MLR: I really wonder what the community of Redditors and bloggers would have to say about your book. A part of me wonders what would happen if they knew how much they impacted you. I didn’t necessarily think of this book as a memoir, but I didn’t do much to obscure things beyond changing some names, and it’s mostly real. Kevin Killian called it a memoir and I’m not going to argue with him. In the book I wrote about a plane crashing in to the Sunvalley Mall and the a “satanic cult” that worshipped in the back of the old ice skating rink. I did a Q+A after a reading in Portland and quipped that both those things were “true.” And then people were like,” wait does that mean the rest of it isn’t?” Which I though was funny. Some things can be verified. A plane crashing into a mall for example. Other things get weird and subjective.

I just read this great comic book called “Look Again,” By Elizabeth A. Trembley, that’s in part about how trauma can interfere/fragment/fuck with our memory. That book is about a capital “T” trauma of finding a dead body in the woods. My book is more about relational trauma, the million times you are hurt by the ones you love, the way you think you get used to it, but what’s really happened is you’ve learned to protect yourself by swallowing your feelings and avoiding the present, avoiding being embodied. I think that kind of trauma messes with your memory too because you have to disconnect from reality just to keep going. While objective reality is important in court cases, fortunately it’s not that important in art. But the phone numbers in the book are real. Call them.

Matt L. Roar is a writer and psychotherapist from San Francisco, currently living in Brooklyn. His writing has appeared in Emocean, JENKEM Skateboard Magazine, Skate Jawn, BOAAT, Ampersand Review, The Surfer’s Journal, HTML Giant, The Poetry Foundation, The Brooklyn Poet’s Anthology, and elsewhere. He is the author of the chapbooks The Shredders (Mondo Bummer) and Probability of Dependent Events (Beard of Bees). His first full-length collection, MY WAR, was released in 2022.

Niina Pollari is the author of the poetry collections Path of Totality (Soft Skull) and Dead Horse (Birds, LLC), as well as the co-author of the split chapbook Total Mood Killer (Tiger Bee Press). She also translated, from the Finnish, Tytti Heikkinen’s debut English collection The Warmth of the Taxidermied Animal (Action Books). She lives in Western North Carolina with her family.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.

Leave a comment