Josh Denslow’s Super Normal tells the story of siblings who possess superpowers coming together as they receive devastating news about their mother. Bradley Sides’ Crocodile Tears Didn’t Cause the Flood explores the southern lives of individuals taking care of pond monsters, running garlic farms, and fighting their dinosaur siblings. With their new books, Denslow and Sides take on family, magic, and love.

The two writers set aside some time to talk about their new books and the processes in which they put them together.

Bradley Sides: Hey, man. It’s good to catch up with you. The first time we talked, it was for The Millions when your debut collection, Not Everyone Is Special, was getting ready to make its way in the world. I asked you about characters, and you said this: “I do indeed write about broken souls, but I tend to think of my characters as superheroes.” You went on to talk more about superheroes and superpowers. I’m curious if you were thinking a bit about Super Normal back then—with the superheroes and superpowers and all?

Josh Denslow: Man it’s so awesome to talk to you too! I went back and read our interview, which was in 2019! Man, that feels like a different life. I mean, we hadn’t even heard the word COVID yet. I didn’t know my hair was about to go completely gray while I attended kindergarten and first grade online with my children! I guess we all became superheroes on some level.

But to answer your question, yes, I definitely had Super Normal on my mind at that time we talked. It was called something different and had some of the same characters, in fact at that point it barely resembled the book now. But the characters in Super Normal were born while I was writing many of the stories that eventually became Not Everyone Is Special, and seeing the novel actually out in the world has brought that part of my writing life to a close. It was like watching a group of really close friends finally succeed. Getting the chance to try one last time with Super Normal after nearly 20 years of carrying it around was pretty gratifying.

BS: I hear so often about people writing novels in a few weeks or months, and I’m always jealous. Your story of working with this book for so long is inspiring. Books can take time! It’s important to have that reminder.

I am curious, though, what was it about Super Normal that made you stay with it—was it something just within you as a writer? Or did it have more to do with this particular novel?

JD: I really liked the characters. I felt I was letting them down by never getting their story right. I owed it to them to stick with it. I hear so many stories of books getting shelved, especially first novels, and I feel incredibly lucky that things worked out the way they did. In the time I’ve had Super Normal with me, I wrote two other still as of yet unpublished novels, and the writing of both of them absolutely helped me figure out what I was doing wrong in all the previous iterations of Super Normal. But with hindsight and all that, I know that there was no way to have Super Normal twenty years ago. It had to be right now for it to work at all.

BS: I’m glad you stuck with it because Super Normal is an absolutely beautiful book, one full of a perfect balance of heart and humor.

I want to ask about the level of humor. How much humor does it take to qualify a book as a comedy? Do you think of your novel as a comedy?

JD: There were two problems with previous iterations of Super Normal. One was that at some point early in the process I became married to a structure that I was unable to deviate from. And the other was that it was entirely too serious. When Stillhouse accepted Super Normal, it was the first time I went back and read it in a few years, if I’m honest. During that time, as I said, I’d completed another novel that had come together exactly how I wanted it. And in that read, I could see what a flawed beast Super Normal was. Stillhouse I know responded to the characters and the situation, but I knew I could do it better. I was finally a good enough writer to get it right. And the first thing I did was kill the structure. It was holding me back. I was writing to a form rather than letting the characters take me where they wanted to go. It was the most freeing moment in the whole process.

But that brings us to the topic of humor. And that old version was way too serious. I had spent some years trying to be a serious literary writer that it was almost embarrassing to see how hard I was pretending. How far away I’d gotten from the voice I’d honed. I don’t write comedies as some people would think of comedies, as you know, but my writing is funny. I think for me most of it comes out in dialogue. Super Normal is really working now because I allowed that humor to permeate the story. I relaxed on structure, and I relaxed on the tone, and suddenly it came alive, jumping toward new interactions and an entirely new ending. It was exhilarating.

But I will say that I sometimes stop short of saying my book is a comedy. Because I think in that sense, people then assume that the serious themes don’t land. Super Normal is not a comedy first. It has plenty of other serious aspirations. It’s a comedy because it’s funny while it goes about its business.

I think both of your collections walk that line too. In particular with Crocodile Tears, humor springs out because of the way you reveal information. But holding some things back, you are playing with our expectations, and we find ourselves laughing at how incorrectly we had gauged the situation. A great example of this is the story “To Take, To Leave.” It has these laugh out loud moments in the form of a choose your own adventure story and the choices we as the reader need to make. Then a few pages later, we realize how devastating it’s been the whole time too. I love that. Talk to me about how you use humor in your collection.

BS: Humor is so hard, I think, to get right, especially for me! It exists and functions on so many levels, and those levels kind of depend on the individual reader to a certain degree.

I was determined for this book to be funny—to make people laugh, or at least chuckle, in spots. I think it really needed that lightness because I’m looking at some heavy stuff like loss and grief. A book of constant sorrow is going to be a rough experience. So, I channeled what I think is funny, largely absurdity, and I wrote it.

There are vampires working on an organic garlic farm. There are all kinds of ridiculous setups at the ends of the world, including in the story you mention. There’s a kid who’s jealous of his sister who is a literal dinosaur bird. I just wanted to give these naturally funny setups and then get heavy with it. Haha! I’m so glad you pointed to how several of the stories play with expectations because that’s exactly what I was hoping for.

You mentioned something earlier that I’ve been struggling with for the longest time, and I have to acknowledge it briefly. You just said an intended structure was holding you back. I was literally just having this issue with my current novel. I kept telling myself that a novel has to have a set structure. Extended chapters and scenes, mainly, but I’ve given myself the freedom to write flashes and vignettes, and this book is so much better for it. I’m channeling Big Fish and Late Migrations, and I’m loving it. Letting my book find its own structure—and not the one I planned—saved it. I just had to acknowledge what you said, and champion it.

JD: Man I love to hear that! As writers, we really do make things harder than they need to be sometimes. Whether it’s forcing our writing into an unnecessary shape or telling our characters to do something that they would never do if they had free will! But one thing you do that I love, is to bring the reader into the mix. Your collection has that wonderful choose your own adventure story, which is the ultimate direct address. But you also have a two truths and a lie, which engages the reader’s brain in different way as they read. And in my absolute favorite story, a boy passing off the care of a lake monster in the form of a letter detailing its care, feels directed right out to me. That I’m the one about to take on this task. How aware are you of this as you go along? How important is that interplay between writer and reader?

BS: I’m glad you connected with “The Guide to King George” like that. It seems to be the favorite story of the collection for many readers. You know, to answer your question, I am aware. As a reader, I like that engagement. That connection. This style translates to how I approach my own writing. I feel like having that relationship with the reader is a way to increase stakes, and it’s also a way to build an added layer of pathos hopefully. It’s not just a story. It’s a story they know. It has some brand of personal investment and interest, and maybe it becomes real, on some level. With magical realism and weird fiction, I think there’s some added pressure to make things real. The interplay is one of the big ways I try to accomplish this.

JD: I loved your collection Those Fantastic Lives. In preparation for this interview I saw the blurb I provided and I feel in a way, I could have supplied the same blurb for this one. I have the same feelings. The stories are still scary and funny and thrilling, and the characters are still doomed. But there’s a cohesion here in Crocodile Tears that latches the stories together even stronger than the previous collection. As you were writing these stories, did you know they were going to be a part of your next collection? Was there any thought given to what story you might write next based on what the collection needed? It moves so effortlessly. I love it.

BS: Thanks, man. I appreciate you saying so. I feel like I’m supposed to say that I didn’t know what would become of the stories, but the truth is that I always had a next collection in mind. My cycle with the stories inside Crocodile Tears began as I was finishing Those Fantastic Lives. In fact, during the same week that my debut was released, Ghost Parachute published “Do You Remember?,” which is a flash about a shark boy on a sad and revealing beach vacation. I present the entire story as a series of questions. With it and with all I was beginning to get ideas for, I could tell I was wanting to experiment more and more. I was wanting to take some chances. So I embraced that. I wanted a collection that was weird in stories, for sure, but also weird in the way I told stories. It felt right for me.

And absolutely! 100%. Having been through the process before of shaping a book, I knew what I needed—or wanted, I should say. When stories were feeling too heavy, I added lightness. When stories were taking place around too much water, which is a common thing with me, I went to farms. I was looking for balance. And I was looking to build that balance from the beginning.

JD: I have to ask, because I think I subconsciously noticed it but never formed it into a thought: What draws you to water? And why do you feel you have to pull back from it?

BS: I feel like my entire life has been shaped around water, so it’s just naturally present I think. My parents live on a farm. There’s a large pond probably 50 feet from the back door. I have so many visual memories of just seeing the cows and ducks and cats and dogs just hanging out. We’d go there all the time, too. On top of the pond, my parents also have a couple of creeks on their land. We’d catch minnows or just sit out and escape the Alabama summer by letting the water run over us. Even now, when my wife and I travel, I’m always looking for water destinations. I just love water, and it’s very much a part of me.

Honestly, I tend to be very comfortable in my interests. I don’t know if it’s a bit of just too much comfort or obsessiveness or laziness. Maybe all three. Ha! But I listen to the same music. The National. Tyler Childers. Sturgill Simpson. Fleet Foxes. I watch the same shows. The way I approach food is the same way. I just like what I like. In my stories, though, I try to be extra mindful of giving variety. A story collection can easily feel repetitive without it, and I want to do all I can to keep my readers on their toes.

I have a structural question for you. Your novel frequently shifts to various characters’ perspectives. It comes across so naturally, and I want to know how you did it. Did you write each character’s story and then go back and piece it together in the larger book? Or did you write it as it appears, where you went back and forth?

JD: I wrote it exactly as it is in that order. I just switched as the story needed it. There wasn’t too much planning. Which was on purpose because I was in that free flowing stage after ditching the aforementioned rigid structure I’d had for three previous drafts and I was having a ton of fun.

BS: That’s interesting. I’m not much of a planner either. Like you, I think having fun while writing sparks something special.

One thing that is so interesting about Super Normal is that I would often chuckle as I was reading it and think about its humor, but when I step back and think about the book as a whole, I also think about loneliness and longing and how these two characteristics shape a great deal of the story here. Edna’s narrative is, at least to me, shaped around a deep sense of longing. John and Denise are incredibly lonely, and they have this really sad (and equally honest) exchange that’s quite tender and bare. He says, “Thank you for picking up my call. I don’t have anyone to turn to. I don’t have any friends.” She replies, “I don’t have any friends either.” The book seems to be a call for connection—for understanding, for love. Right?

JD: I could absolutely say the same thing about your collection. Your characters are looking for connection too. But you really up the stakes. In one story the want of a child that falls from the sky brings about the apocalypse! There’s a boy caring for a monster in a lake, and when he wants to leave, he’s trying to find someone else to give the same level of care. And that praying for snow story. Man, there’s a line in there that I think reveals what’s really at the heart of your collection. Each time he prays for snow, he’s waiting “for those he loved to wrap their arms around him again.” And I think it’s the same in my book. We all have people in our lives, but how do you connect with them? How do you feel safe and comfortable and somehow not terrified?

BS: True. True. Those are the questions! The BIG questions! In life and in my stories, death complicates things. Death is coming. That’s the terror. This fact seems to drive connection, but it also shows that a disconnection is inevitable. It’s both beautiful and sad.

Both of our books engage with the fantastic, and they both also reject this magic as being a form of absolute salvation from the real world. In your book, with the siblings’ powers, this bit of magic is helpful at times, yeah, but it’s also, at times, a burden to carry. A big burden. Life is like that, right? The seemingly magical is great, but it alone can’t save us.

You wrote a novel about siblings with superpowers. It’s only right that we end our talk with our own dream powers. I’d want to fly, but I’d only want to fly like Linda from The Good Place, grouchily hovering a few inches above the ground. I just think it would be funny and ridiculous. Having a brilliant ability and just barely, barely using it. How about you?

JD: It’s funny, but I think I would pick flying too. But for me, I’d want to be the best at flying ever. Higher and faster than any other flying creature. Just this amazing flyer. And let me tell you, everyone would know about it. Everyone.

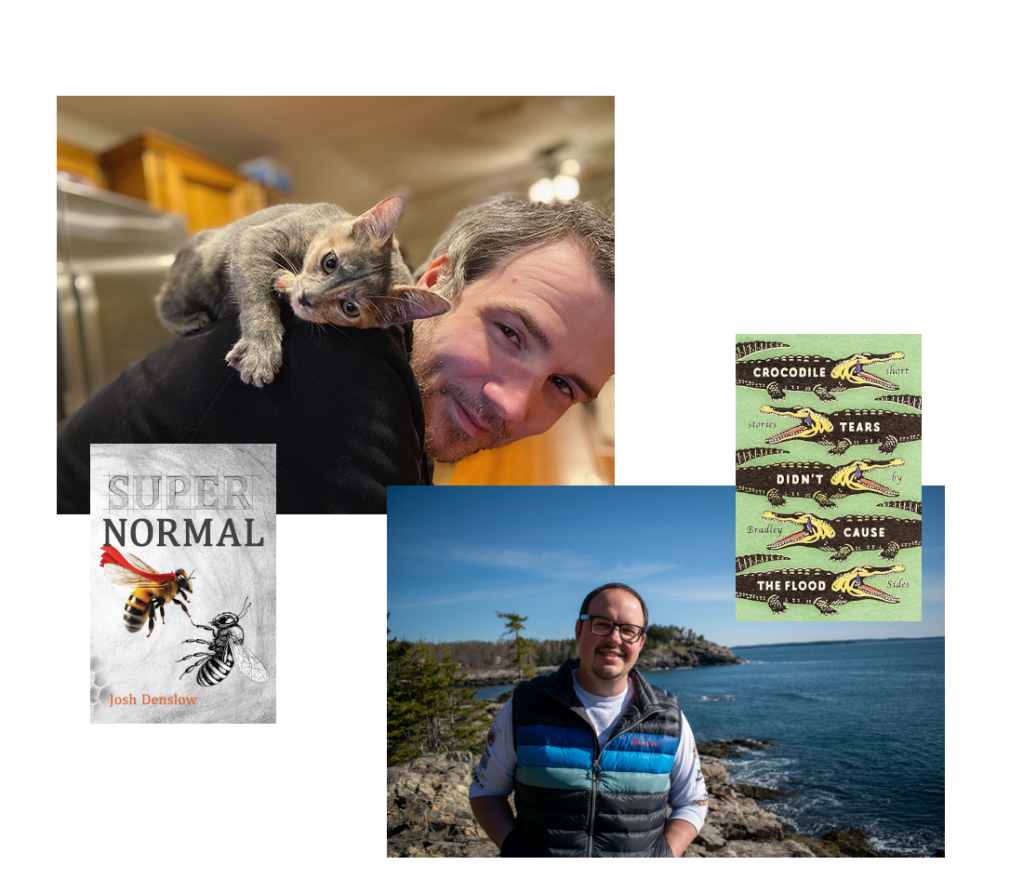

Josh Denslow is the author of Not Everyone Is Special, Super Normal, and the upcoming collection Magic Can’t Save Us. His most recent short stories have appeared in Electric Literature’s The Commuter, The Rumpus, and Okay Donkey, among others. He is the Email Marketing Manager for Bookshop.org, and he has read and edited for SmokeLong Quarterly for over a decade. He currently lives in Barcelona.

Bradley Sides is the author of Those Fantastic Lives and Crocodile Tears Didn’t Cause the Flood. His fiction has been featured on LeVar Burton Reads. Currently, he lives in Huntsville, Alabama, with his wife, pup, and two cats. On most days, he can be found teaching writing at Calhoun Community College.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.