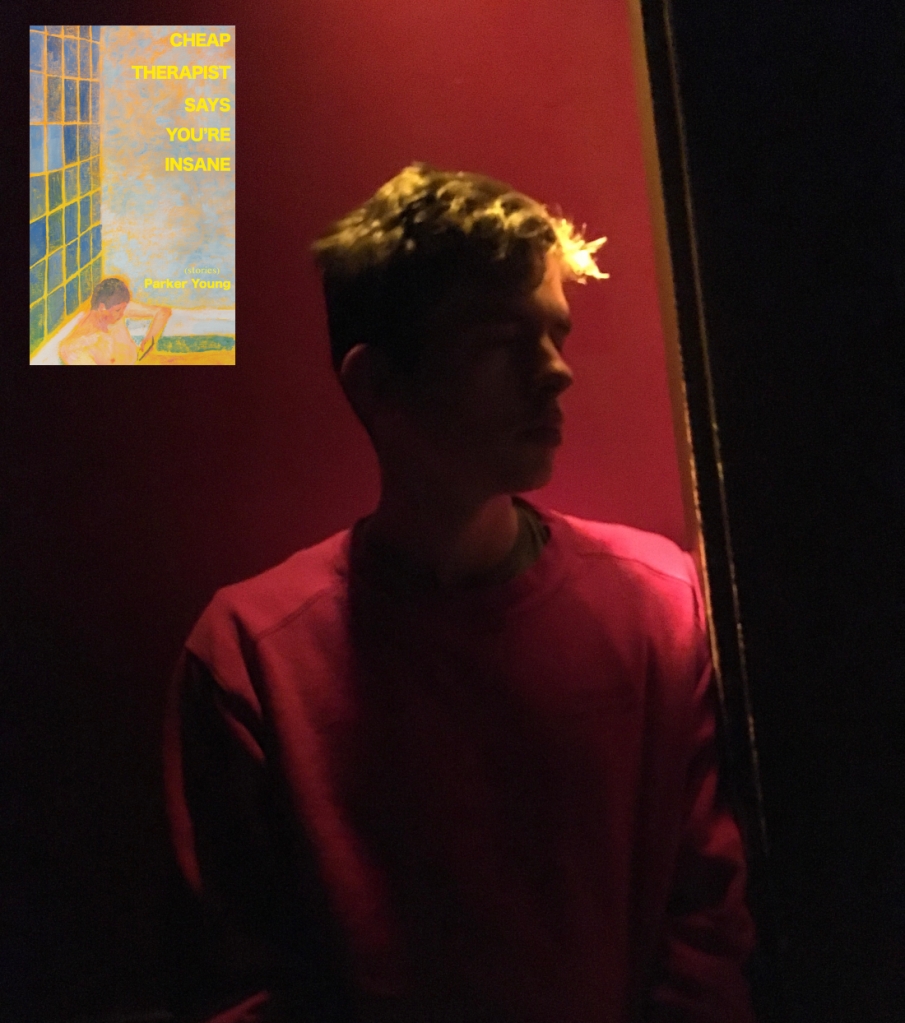

Cheap Therapist Says You’re Insane, out now from Future Tense Books, is the rare short story collection that provides shockingly robust pleasure from the beginning to the end, the kind can only exist in the shadow of deep discomfort. This book is all killer, no filler. Young’s prose, without ever losing its root in the heart, depicts the absurdity of death with dark humor, and the pain of human connection with a light melancholy. Often he does this in just one or two pages. Cheap Therapist Says You’re Insane is full of wild satire and feeling dialogues and illuminating discourse on what we are doing when we are writing. In a pointless world what is this meaning we are trying to make, and why. It is a book I have read compulsively and with delight many times now, and each reading experience always provides me with an aching love for the tragedy of living. Its prose is effortless and enviable. It is a masterpiece of duality so willing to sit calmly in the uncertainty of a bizarre world. Parker agreed to spend some of his time with me discussing his choices.

Sam Heaps: Hi Parker! I’m here and ready to get started whenever.

Parker Young: Hi Sam! Good morning!

SH: Good morning too! I’ve never done an interview on Google Docs before, it is effective and disturbing—not totally out of line with the experience of reading your book. Which, is an absolute and complicated joy. Before we get started I want to reiterate how much I admire this collection and how much I appreciate you taking the time to talk.

PY: Yeah this is pretty weird huh? But thank you so much, I really appreciate you doing this. And I was re-reading some of your book this week too and was impressed by it all over again, it’s really unique and beautiful.

Also I’m worried something is wrong with my coffee, like they gave me decaf or something.

Might have to make more. And I’m watching the kids right now because Rachel isn’t up yet, so apologies if I get distracted or whatever.

SH: No please, children and coffee take precedence. And honestly that could be a nice place to start—there are so many aspects of this book I want to ask about, but one that comes to mind early is the way you capture interpersonal relationships, platonic and romantic … barflys and bartenders … the individual’s relationship to the state—and the title sets this text up as relational, and investigatory of our dependence on others, so well. Would you want to talk a little about how you depict connection, or the ways in which your lived life infiltrates your fiction?

PY: I think that my characters tend to struggle a bit to connect with one another, they talk past each other in conversation, mishear and misinterpret one another, and I’m not sure exactly why I do that. Part of it is probably because I enjoy the tension it creates, or maybe because it’s funny. But I think writers tend to be a little bit suspicious of language by nature, if that makes sense, they have some sort of fundamental issue with it. In my everyday life, I usually don’t have time to indulge those concerns. But in my art, I’m free to worry over it and obsess and try to work out the implications. I’m not sure that’s helped me in any sort of practical way. But it is important for me to have a few people in my life I can really trust, people I can talk to without worrying about a trapdoor opening up. I guess I’m really just talking about my wife here and a few friends. And of course my kids, but that’s on another level and even more difficult to understand. But this might be a fundamentally antisocial response to your prompt, I don’t know.

SH: Your image of the recurring trapdoor—it makes me so grateful to have the collection. That you write when there is this correctly assessed (I think lol) constant threat and you are still willing to be vulnerable on the page. For such a funny collection I cried often reading it with just overwhelm, often because of those missed communications and inarticulable experiences. Your answer doesn’t sound antisocial to me at all, it sounds, and I’ve called your book this before, wise. And also a little romantic.

It makes me want to go back to your earlier comment about writers being suspicious of language. The one two punch of the stories “May 24” on page 102 and “Writing Fiction” on page 106, made me say, fuck you, very loudly in public just struck by how right they feel. “Writing Fiction” in encapsulates so well the inane and desperate experience of making art. “Writing fiction is like trying to figure out who ate the salami by eating salami” … “It’s like experiencing real grief when your attempt to fuck the snowman makes it melt.” As a private, not antisocial but correctly mistrustful person, what drew you to fiction in particular as a form of attempted communication?

PY: I guess I’ve always been drawn to narrative art, and at some point maybe I realized that writing fiction is really the only way to make that kind of art without tons of money and the cooperation of a lot of people. And the connection you have with a novel or memoir is just different, more intense and personal somehow, than with other types of narrative art because the author is never too far behind the curtain (unless they’re edited to shreds or something). But the real answer is probably that I don’t know why I started writing fiction, it was just something I decided to try about ten years ago, and instead of giving up I just kept going.

But since we’ve been talking about language, I wanted to ask about your book, which is organized around descriptions of sex, which is something most writers avoid because, I think, it’s so hard to do well—it’s almost impossible to illuminate that experience with language, like a black hole or some other phenomena that physicists suspect exist but don’t know how to measure. Your book takes on that possibility with a reckless abandon that’s really breathtaking, and for that reason it leads to a portrait of a life that’s totally unique. Were you consciously writing into that impossibility when you decided to start this book?

SH: I love that admission to just going. So much of writing I feel it is equal parts reliance and tenacity that stems from maybe an unhealthy dependance on the art.

You ask if I was writing to an impossibility when I was writing about sex. I guess I also love how often your characters go unseen because my book feels like such a desperate attempt to be witnessed by someone I wanted. I think if you really know it is impossible, you can’t try? Part of me had to have hoped I could grab a tuft from the black hole and transfer my experiences and be seen. And it was ultimately a failure for me lol. So I admire you writing around that failure with full admission?

“On the Toilet” is maybe the first story to directly reference suicide, and you quote Virginia Woolf saying her intended suicide is the only experience she would never describe. I want to talk about this other kind of experience that can’t be touched really in words, that of emotional pain. It is a gift to have writers depict pain gracefully, to me. Would you like to talk at all about your choices here? “Carbon Monoxide” ends with a door that can’t do the job of a door. In “Proximity” I ask often what the purpose of a body is, and the agonizing absurdity of its limitations. In my margins I have written on page 43, does Parker have the answers?

PY: I definitely don’t have any answers. And I don’t know how much I should say here about my choices, because a lot of it is just an expression of some sort of aesthetic preference I have, an ideal I’m chasing which may not speak to everyone. I guess that I want my stories to have stakes, but I also want to preserve a sense of play or lightness. When a story has both, that’s when it feels alive to me. But it means a lot to me that you found an element of grace in the work. I can’t ask for much more than that.

SH: Okay fair enough. We talked a little sex, pain, now money? (I think we left out drugs.) I had a hard time placing your book’s relationship to class as I was reading. Sometimes your characters were broke sometimes they were monied. I admired your ability to make me care pretty generously and transcendently.

PY: Money is good fodder for stories because it can be an embarrassing thing for people to talk about, either because they think it’s their fault they don’t have it or because they have it and don’t want to think about why. Especially in the world of literature, where very few people actually turn a profit on their time, money takes on an almost mythological aspect, nobody knows exactly how to make it or where it comes from or why certain people have it. And because success in publishing is so ambiguous and often seemingly manufactured, money becomes even more alluring since it’s measurable. So it’s fun to play with that tension in fiction, and now that we’re talking about it, I wish I’d done more of it.

One more question about “Proximity.” On page 125, you seem to express skepticism regarding fiction writers who “take credit for the actions of others. As if you invented my madness and I did not carry it into your kitchen,” and then go straight into an incredibly intimate and specific scene from a relationship, or maybe the end of one. It’s a paragraph that really exemplifies one thing I love about your writing, which is the fluidity you have, the ability to start a paragraph with a riff on the ethics of autofiction and close it with complicated sex and tears and a Corona. But I’m also curious to hear more from you about the power struggle that happens when writers write about people they actually know, including other writers or artists. Do you think that it can be done well in fiction if the writer has enough style to make the depiction transformative? Or is memoir always the more ethical approach for you?

SH: So … as a reader and as a writer I much prefer fiction. I like to see the world shift and distort in wilder ways than can be easily accessed in memoir, and I think of course a stylistic transformation of experiences illuminate real truth. My issue with certain fiction, particularly autofiction writers, is often they are writing something boring (to our conversation around class) or something cowardly. By cowardly I mean it is easy to transcribe an experience without altering it, say you invented it, and release yourself from vulnerability or culpability by relaying it as a fiction. I admire essay writers and memoirists who take full credit for their actions, despite there being very real consequences to sharing these experiences. And I am mostly proud of myself for doing that in “Proximity.”

You mention fluidity in “Proximity”—something I was struck by in Cheap Therapist Says You’re Insane is your ability to depict time passing. The sentences are bare and perhaps because they do not linger so effectively move us from one moment, one day to the next—then also throw us sliding door realities.

Your book’s final line is about storytelling itself:

I tried to remember their names, the names of the people killing themselves, but I kept coming up with the names of my twitter enemies instead, unless they all had the same names, which would be strange—the kind of thing you only encounter in fables and folktales, parables and wild yearns, the world of coincidence, lies.

Your lies always brought me closer to the world, to the feeling of it. What do you feel the limitations of storytelling to be that you bumped against, and I feel quite often transcended?

PY: I guess the limitation is just the medium itself, language, which is probably why I enjoy warping or complicating the stories I tell at some level. Denying certain assurances, as you said. But there are a million different ways of doing that, from Cervantes to Lydia Davis, and in some ways I think it’s just a baked-in part of the job, an essential part of the ongoing conversation that makes up literature. But this is just a convoluted way of saying that writing can be art. Which everyone already knows.

SH: Is there anything else you would like readers to know about? What are you reading these days, and what are you most excited for, for Cheap Therapist Says You’re Insane, or other upcoming projects?

PY: Earlier this year, I discovered that I really like Cormac McCarthy, a writer I felt I didn’t have time for when I was younger. When I realized that he can be funny, it somehow unlocked his whole project for me. As for my own projects, I’m excited to try something new, experiment a little, see if anything sticks.

Sam Heaps is a genderqueer writer and visual artist whose debut essay collection PROXIMITY was released earlier this year. You can find more of their work at TBQ, Write or Die, Communion Arts Journal, and many other wonderful journals. They teach writing at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.