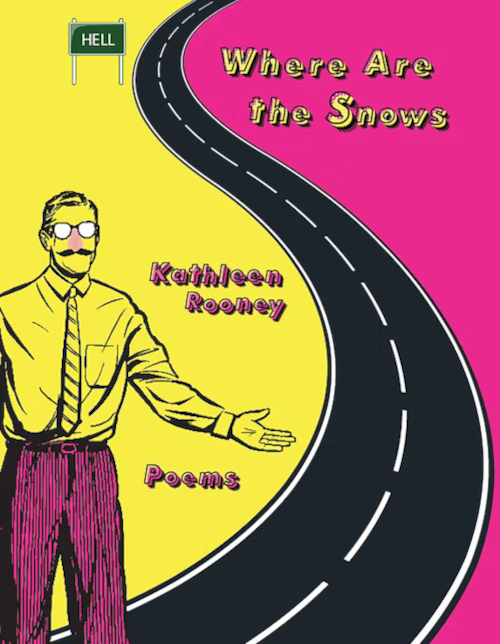

As the cover suggests, these poems are a winding wry road towards the hell Rooney, almost delightfully, explains is Earth, where the speed bumps are humor, the billboards politics, and the golf-ball sized hail is spirituality. The landscape speeding, yet somehow also wallowing, by is peppered with memories, humor, philosophy, and good ole nihilism: “Sometimes a friend posts a photo of their newborn and it’s all I can do not to type, / Welcome to Hell!”

Winner of 2021’s X. J. Kennedy Prize for poetry collections, forty poems comprise the book, each centered around a theme; for example, one of my favorites, “The Sweet and Fleshy Product of a Tree or Other Plant,” is all about the sweet and fleshy products of trees or other plants, well, the specific ones that live in Rooney’s grey matter. This poem houses many of one of my favorite aspects of this book: delights. Here are a few examples:

My sixth-grade teacher’s grandmother held a grudge against bananas. When she immigrated from Poland, someone at Ellis Island handed her one but didn’t show her how to eat it. She choked the whole thing down, peel and all.

Or, from “To Celebrate the Anniversary of Someone’s Birth,” “Mayonnaise is my favorite secret ingredient for cake, birthday or otherwise,” or even this quote from “The State or Period of Being a Child,” where Rooney quotes Iona and Peter Opie from their book on fairy tales, “A child who does not feel wonder is but an inlet for apple pie.” Clearly my delights are food-motivated; however, there are many others not fit for human consumption. These tidbits are the occasional roadside drive-thru milkshakes on the road to hell. (And, to be clear, the gumption and grit needed to eat an unzipped banana is the delight, upcycling mayonnaise is the delight, the idea that wonder is the sole responsibility of a child is a delight, and that the opposite of wonder is gulping down apple pie is not a delight.)

At the other end of these delights is the politically skewed, abject, existential nihilism, draped over the poems like a blanket of somehow delicious-looking magma. In “How to Act,” a poem towards the beginning of the book, this tone is clearly set: “My longing is to perform so well that in the end I’m lashed to death by flowers from the crowd . . . . / What do I do now? Someone tell me what to do.” And later on, a few zingers: “Belinda Carlisle sang that heaven is a place on Earth, but half our nation would prefer to make it hell,” and “New Orleans, New Zealand, New Mexico, New England—pure unoriginality? Or an attempt to improve reality—to claim some of the traits of home, only better? New America, anyone?” Rooney even offers a simple solution to the terrors of capitalism: “I can easily imagine the end of the world and the end of capitalism. / Can’t wait to catch you on the other side, where the blank page holds its breath and waits.”

This progressive nihilism is then paired bewilderingly with Catholic references galore, and, as my childhood was similarly galore, personally, this internal mix doesn’t seem so alien after all (unless of course the underground zeitgeist suspicions are truth, that Jesus hails from an extraterrestrial, celestial above—and if so, I hope he looked like Kirby). After dissecting the Catholic prayer “Hail Mary,” one of the lines introduces us to the idea of Jesus as the fruit of his mother Mary’s womb. And, folded into some advice that would likely have served Rooney’s sixth-grade teacher’s grandmother well in her moment of need, Rooney writes these lines:

When life gives you bananas, make banana bread.

When agriculture collapses, fruit is what I’ll miss the most.

Is Jesus the last fruit I should think of before I’m dead?

In a poem about priests, or, “One Authorized to Perform the Sacred Rites,” we see a similar mix-up progression, “I might still be Catholic if they let women be priests. I might still be Catholic if they let me be a priest,” then “Outside now in the gray daylight, life and death do-si-do as usual. Faith makes the facts less maddeningly casual,” and finally, “We should be searching for a priest who can perform an exorcism on America.” In real time, through the process of this compilation, we get to watch the author continue to grapple with the realities and differences between a desire for spirituality, her American surroundings, and her political and moral beliefs. The grapplings of a person borne to a system rife with contradiction.

At a language level, Rooney has the ability to string a beat of words together whose music means more than their meaning. In “Ekphrastic,” we have “Humans illumine a room with a glow,” and in “To Celebrate the Anniversary of Someone’s Birth” there’s the Seussian, “A rush of Orange Crush—that sparkle on the tongue—and ‘Make a wish!’ shouted at the top of tiny lungs are a couple of things I recall. Balloons and streamers and the first piece of cake. Conical hats with elastic chinstraps.” Quoting once more from the priestly poem, “Like gold brocade on a priestly garment, ritual renders the everyday festive,” and finally, in “Ubi Sunt,” “Yester as a unit, the unit of yester: Yesteryear, yestermonth, yesterweek, yestereve. / Yesterhour yesteryminute yestersecond,” for me, the beauty is in that yester(y)minute-y “y.”

At times, the words’ music glimmers in the ghosts of a smoky room, a bongo drum, and a beret, and although I enjoy the wordplay and the vulnerability of free association, I can’t help but hear it in the syrupy spoken-words of an indoor-sunglassed beat poet. Lines like “The deer here seem to hold the dead very dear, grazing near headstones to leave the carvings clear,” and “Graveyard shifts. Shifts in perspective,” from “A Place Set Aside for Burial of the Dead,” and “Who will write the moral history of my generation? Divination. A divine nation,” from “Foretelling the Future by a Randomly Chosen Passage from a Book,” pull me back to photos I’ve seen of fifties-era coffeehouses.

At times, also, these words can be syrupy and cloying—purposeful or not is up for debate. For example, “When somebody asks, ‘What gives you hope?’ at first I don’t know. Then I think: a house wearing a ruffle of white hydrangeas. The way the moon is in love with the sky. A golden evening, a dreaming sea, and thee,” from “To Cherish a Desire with Anticipation.” Although it’s heartwarming to see a flash of hope on the way to hell, you almost wish to tumble from the serenaded balcony you seem to be standing on, for these ode-ish moments speak not of the waters of existential nihilism in which we have thus far learned to swim. In other words, these tone changes feel out of place, especially few and far between as they are.

While we’re beleaguering the syrupy sweet, let’s also not: “Certain return addresses feel like Pop Rocks in my heart,” a line sugared solely by the Pop Rocks and one of many lovely, tangible images created by Rooney that ask the senses to make conclusions of their own. In this category we have also, “Rainwater drools from the mouth of a gargoyle,” “I like it when kids run around like crazy-craze and tell me they want to be paleontologists,” and “The sunset smears honey for us to stick our dreams to. / I hope that we’re all feeling better soon.” Oh, and “A solarium can be a cube of sunshine and enlightenment, like living inside a Funfetti cake,” from “A Building That Serves as Living Quarters.” There are too many to list. In context, these images mean more, and detached they’re worth considering for their own merits.

These images are much like the different birds we encounter throughout the compilation—goldfinch, cardinal, hawk, seagull, goose, tanager, pigeon, a flattened hermit thrush, a robin, etc.—all worth being considered for their own merits amidst the backdrop of existential nihilism that disregards the individual. Yet, in lieu of Rooney’s sign off, “We must do more than idly talk. We must become a flock of smaller birds attacking a hawk,” maybe these birds mean more than themselves. And now, I’m left wondering if Rooney’s road to hell really just highlights the importance that there even is a road at all, all of us just “Bunnies, bunnies everywhere! Like big plump hopping loaves of bread.”

Where Are the Snows, by Kathleen Rooney. Huntsville, Texas: Texas Review Press, September 2022. 73 pages. $21.95, paper.

Esa Grigsby is a Portland-based editor, writer, and farmer whose work can be seen in Entropy, Kind Writers, The Rumpus, and at esagrigsby.com.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.