Over the past few years, as I’ve delved further into indie and experimental literature and been exposed to the dazzling array of queer writers thriving therein, I’ve discovered something of a bad habit in myself—a tendency to automatically read as-yet-unidentified narrators as the same gender as their authors. I’ve been caught with my comprehensive pants down more than once, mentally misgendering first-person protagonists for pages at a time before coming to realize that I was picturing characters wholly opposite from, or at best, far less complex than what their creators intended; reflexively oversimplifying the very matters they were patiently, painstakingly working to elucidate to my basic-ass binary mind. I’m not proud of it—this snapback straight guy paradigm I fall into—and once I realize my error I generally scold myself, tuck my tail between my legs, and start whatever story I’ve misread over from the top, at least attempting to correct my perspective accordingly.

This gets exponentially harder, however, when it comes to Joe Koch. Not because their voice is unclear, but because it so fiercely resists the tethers of uniform interpretation. No one is exactly what they appear here. In fact, no one is exactly any one thing at all. Rather, these are tales of violative transformation and irreparable transcendence; of cagefights and waxwings; of bodies and Gods. With this writhing, groaning, blood-lubed groupfuck of a collection, Koch has pulled off the seemingly impossible feat of both never doing the same thing twice, and doing everything they could possibly think of all at once. If sexuality is a spectrum, then Joe Koch is a prism. If gender is a construct, then Joe Koch is a destroyer of worlds. You don’t even know yet how much you don’t know.

I first encountered Koch’s work via this book’s titular story, which originally appeared in Chris Kelso and David Leo Rice’s indispensable David Cronenberg anthology Children of the New Flesh (11:11 Press), and its inclusion in that tribute compendium to the impresario of body horror makes even more sense upon rereading it here in its natural surroundings. Kaleidoscopically revolving around two captives in some futuristic prison-cum-human-processing-plant, it serves as both a natural portal into Koch’s singularly disorienting, splatterpunk-by-way-of-Baudelaire style, and a gracious warning bell to those who might not possess the stomach for such fistular poetry. Both the shortest and densest piece in the book, its six tight-packed pages read like a dirty bomb waiting to go off; to cave in ceilings, collapse floors, and break the wheel of our cyclically consumptive society; a bomb set to “fuck this building so hard it falls to the ground.”

For those who survive this initial blast, “Bride of the White Rat” offers a breather from Koch’s bunker buster linguistics, but may still leave you hyperventilating by its conclusion, as it conjures a grimly tragicomic grotesque of right-wing paranoia—an unhinged young man so gnarled by hate (and almost certainly self-hate as well) that he feels compelled to don ill-fitting womenswear to prove his inviolate masculinity, and fabricate a 1984-inspired rattrap facial contraption to further test his mettle against whatever liberal queer apocalypse he fears is heading his way. Told through the eyes of his parlous kindhearted girlfriend, and intercut with some hideous details regarding the rodents used in Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu, it flips the script on the MAGA trend of dehumanizing marginalized people groups as vermin, reclaiming and redeploying the metaphor for the insidious fascism-creep America’s been slow-playing at least since Trump first descended that golden escalator nearly a decade ago (if not since 9/11) (if not longer still). The most straightforward (and straight) narrative Invaginies has to offer, “Bride of the White Rat” functions almost as a second beginning—a depiction of the traditional male/female binary at its most toxic and corrupt. If “Invaginies” is the incendiary by which Koch sends us back to the stone age, then “Bride of the White Rat” is the stone age upon which they must build.

And build they do. For within the synesthetic hyper-collage of stories that follows, quite literally nothing is off limits. “I Married a Dead Man” traces the lonely, post-traumatic pursuits of a young queer hustler working the docks night after night in search of the shame-closeted father who abandoned them. “Leviathan’s Knot” puts you inside the agonized mind of a female heretic being burned by Christians at the stake, only to achieve ascendancy through recombinant unification with the male God she refused to renounce. “Eclipse, Embrace” evokes the spirit of Angela Carter, interweaving werewolf and Red Riding Hood folklore in a revisionist tale of queer love and survival. “All the Rapes in the Museum” recounts an ecstatic ménage à trois between a seraphic statue, a witch, and an Iron Maiden. And “Convulsive, or Not at All” skips across eons, from the hulking desert deity Amon to an omnisexual starship princess preparing to birth the void and return the world to chaos once more. In a way, this story contains the whole massive scope of Koch’s enterprise writ small. The past is but a mythology to dismantle; the future, a science fiction to realize and explore. And the present in-between? A liminal goulash of undiluted horror. The horror of all that must happen before we finally evolve ourselves whole.

Perhaps the scariest aspect of reading Invaginies is the way in which it begins, after a time, to unmoor you—from time and history, from plot structure and genre, and from your own senses and feelings about your body; a nauseous literary approximation of vicarious gender dysphoria. But through the comparatively wider lens of the queer experience, and their sorcerous smithery of bent and battered language, Koch at least effects a vision of a different kind of world—a better tomorrow we can see, even if we can’t yet comprehend it—as though painting fantastical landscapes directly upon our brains. And with the book’s longest, and final story “The Wing of Circumcision Hands” Koch arguably threads the last suture closed on their own human centipede of nested narratives. Set within a vast, underground cathedral—a sentient network of chambers pulsing with profane iconography and organic theatre screens (which may well be projecting every story you just read upon its throbbing walls)—it’s part museum heist, part Videodrome dungeon. And as its twinned protagonists—shackled at the wrist—are drawn deeper and deeper into this cavernous “angel trap”—bearing witness to a Grand Guignol finale to rival The Broken Movie, Guadagnino’s Suspiria, and every Mortal Kombat fatality ever executed—it becomes easy to imagine them as the very same pair of anonymous prisoners plotting terroristic escape however many years later in the book’s opening tale. It’s as if Koch is trying to remind us, one last time, that while these cycles of confusion and enlightenment, subjugation and resistance, violence and empathy, are ongoing and quite possibly infinite, that in no way devalues the work of breaking them. That “the more one searches for meaning or narrative, the less there is.” That we must always keep the big picture in mind, and remain willing to start over again.

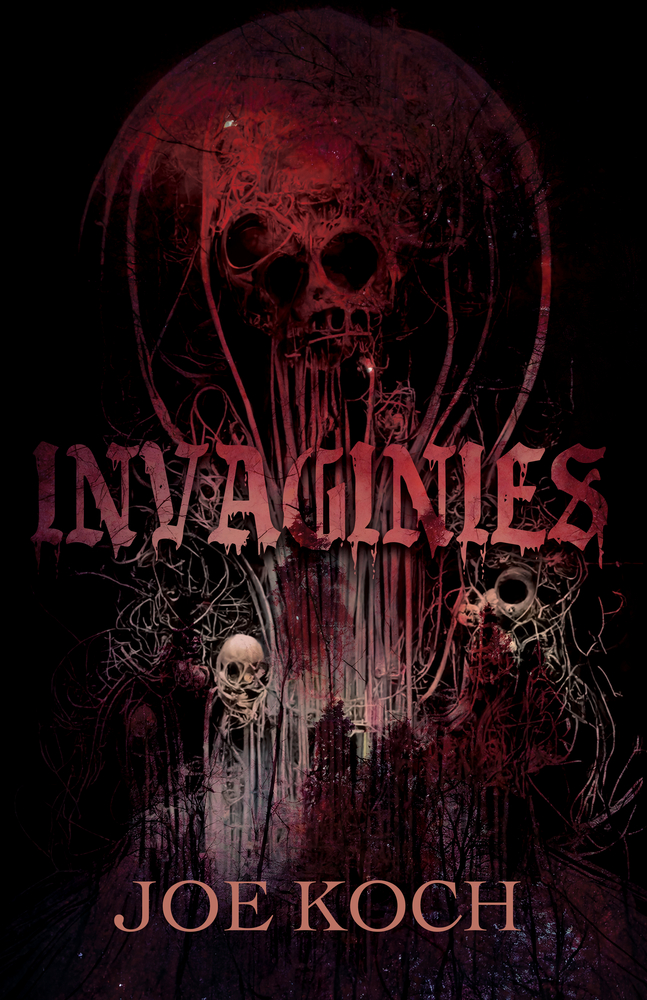

Invaginies, by Joe Koch. CLASH Books, June 2024. 238 pages. $16.95, paper.

Dave Fitzgerald is a writer living and working in Athens, Georgia. He contributes sporadic film criticism to DailyGrindhouse.com and Cinedump.com, and his first novel, Troll, was published in May 2023 by Whiskey Tit Books. He tweets @DFitzgerraldo.

Check out HFR’s book catalog, publicity list, submission manager, and buy merch from our Spring store. Follow us on Instagram and YouTube. Disclosure: HFR is an affiliate of Bookshop.org and we will earn a commission if you click through and make a purchase. Sales from Bookshop.org help support independent bookstores and small presses.